By Steve Beaven

For Ignite Magazine

Gloria (not her real name) came for a free eye exam on a warm, cloudless summer afternoon last year.

A chatty grandma in her early 70s, Gloria was nearly blinded 35 years ago in Mexico when hot cooking oil splattered her left eye, leaving her with blurry vision. She later escaped an abusive marriage and moved to Salem, Oregon, in 1994 with no job, no insurance and a left eye that wasn’t going to heal itself.

Last July, an outreach coordinator with Northwest Human Services, a Salem nonprofit, helped Gloria schedule a vision exam with the OHSU Casey Eye Institute’s 33-foot mobile vision clinic when it visited their city. She arrived for her 12:45 p.m. appointment, talked with friends and strangers alike, underwent a thorough eye exam and made sure to express her thanks before she left. She lives with her daughter, Carmen*, and relies on her for financial assistance. The free exam helps preserve her eyesight and saves her family money that can be spent on food and other necessities. Because the clinic came to their community, Carmen and Gloria didn’t need to coordinate travel to Casey Eye’s location in Portland.

“She believes in God and she’s very positive,” Carmen said. “And she’s very grateful. This is a big help.”

Eliminating preventable blindness

In rural areas and underserved urban and suburban neighborhoods, eye disease is often invisible and untreated, a slow-moving medical catastrophe if not diagnosed in time. Residents in these communities face barriers to care and a greater risk of eye ailments because they, like Gloria and Carmen, frequently endure systemic barriers that can result in limited economic mobility and poorer health outcomes. In small towns and rural areas, there might be few, if any, vision specialists. In urban and suburban areas, residents may have little access to cars. Often, these community members are also underinsured or have no insurance at all, and thus no way to access vision care. Retired ranchers from Burns or farmworkers from Hermiston aren’t likely to drive hundreds of miles to Portland for an eye exam. An elderly couple in the Willamette Valley may feel that vision care from Casey Eye providers isn’t available to them.

That’s why the OHSU Casey Eye Institute created the Community Outreach Program. For more than a decade, the mobile clinic Gloria visited has been the anchor for the program. The mobile clinic — an

enormous ophthalmology exam room on wheels — has zigged and zagged across Oregon to nearly every county in the state, from Multnomah to Malheur and Hood River to Harney, to provide free eye screenings and prescription glasses. The program is largely staffed by volunteers, including Casey Eye doctors, all working toward the same goal: eliminating preventable blindness in Oregon.

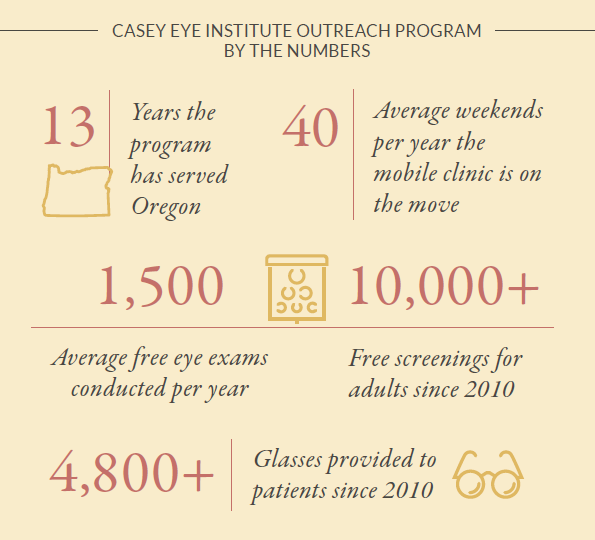

Philanthropy has made every aspect of this program possible since its earliest days in 2010. Initial funding from Heather Killough, the Roundhouse Foundation, the Oregon Community Foundation and Schnitzer Steel brought volunteer eye doctors, technicians, students and community members together in nearly every corner of Oregon. In the program’s first decade, the mobile clinic hit the road nearly 40 weekends each year, did an average of 1,500 free exams, offered more than 10,000 free screenings for adults and provided more than 4,800 pairs of glasses.

“The success of the Casey Community Outreach Program has literally changed lives,” Killough said. “Many of the program’s clients live in rural areas far from necessary health care services; others are underinsured. Had it not been for the program, these individuals simply may not have been able to access care and experience increased quality of life.”

Killough is furthering the Casey family’s impact on OHSU. Her grandfather, Henry Casey, and his sister, Marguerite, helped fund the construction of the Casey Eye Institute building in 1991. Several generations of the Casey family, in fact, have made generous gifts to Casey Eye for more than three decades.

Widening the lens of vision care

Casey Eye is now in the early stages of building a far more ambitious project, a substantial expansion of the Community Outreach Program designed to achieve three very specific goals: 1) reach more Oregonians in need of vision care, 2) build a new level of local expertise in underserved areas and 3) use emerging technology for faster and more efficient treatment. It’s a community-centric approach and, if it can be replicated, it could change the way vision care is delivered in communities across the country. And just in time; the prevalence of blindness in the U.S. is expected to double in the next 30 years.

OHSU had planned to unveil the expanded program in 2021. COVID delayed that plan because the program’s community partners were overwhelmed with caring for vulnerable populations during the pandemic. There were fewer community visits, which made it more difficult to work with local social service agencies to establish new telehealth sites. Some of the outreach coordinators at those agencies moved on to other jobs.

“It’s taken us a while to get this [expansion] up and running because our partners have been so focused on the pandemic,” said Verian Wedeking, the program director.

But now that pandemic restrictions have been lifted, OHSU has begun building its outreach network again and adding more telehealth sites. The program has also added staff, including a full-time research manager and training and outreach specialists.

At the heart of this plan is the vision to bring the full diagnostic prowess of a world-class eye institute to Oregonians, wherever they live, and to connect individuals found to be at risk of losing sight with ongoing eye care as close to home as possible. The expansion is, essentially, the marriage of two disparate and sometimes conflicting elements of modern health care: advanced technology and community engagement.

“I think it’s a fundamental requirement to have these two things working reasonably well together because either approach alone is not good enough,” said Mitchell Brinks, M.D., M.P.H., medical director of the outreach program and associate professor of ophthalmology in the OHSU School of Medicine.

The expansion will meet even more Oregonians in their own communities. The aim is to increase the screening capacity in each telehealth location from 40 individuals a year to up to 500 individuals. Additionally, the program is building a second mobile eye clinic. This new clinic will be even bigger than the first, providing more room for new imaging equipment and more privacy for patients. It’s due to hit the road in the fall of 2023. (Editor’s note: Read about it in our 2024 impact report.)

Building local expertise

The reconfigured outreach model will include far more than a second mobile unit. The Community Outreach Program is determined to make quality eye care a permanent fixture in their partner communities. Doing so has required a shift in mentality, from individual health services to population health care.

First, Casey Eye built on the community coalitions it has worked with throughout the state to create the Oregon Vision Health Network (OVHN), a group of local agencies that work with the Casey Eye Institute at more than 70 telehealth sites.

Second, the program is bringing community health workers onboard, expanding their roles and training them to conduct initial examinations before the mobile clinic arrives. The Casey Eye Institute developed the training; it was approved by the Oregon Health Authority Office of Equity and Inclusion.

“One of the things that’s important is that when people come into that clinic, they see a familiar face.”

Verian Wedeking, Program Director

Since 2021, about 60 community health workers from 28 agencies have been trained as Vision Health Navigators. They provide preventative education, perform basic vision screening and coordinate follow-up care. They’re able to screen for diabetic retinopathy and other common eye diseases and pinpoint social and environmental factors that increase the probability for blindness. They also direct participants to additional care at the mobile clinic and to the offices of eye doctors throughout the state.

“It is truly a beautiful thing to see different organizations work in unison, motivated with the same passion of providing respectful, excellent care,” said Dove Spector, the program’s community outreach research manager.

It’s a true team effort that requires each and every member to contribute in a meaningful way. The hosts and staff in each community are especially critical to the program’s success. They’re on the front lines, and they know participants and their families better than anyone.

“I prep the doctors in advance to say, ‘Hey, this individual is going to be seen at this clinic for a comprehensive eye exam,’” said Memo Plazas, who handles outreach for Northwest Human Services in Salem and scheduled the appointment for Gloria. “If they find something, it’s my responsibility to make sure that individual is referred to the specialty care that was recommended.”

Staff from the community health centers — and community health workers, in particular — will be the public face of the OVHN. Their presence will build trust and help bridge the gap between the community and the specialized medical care provided by the Casey Eye Institute.

“One of the things that’s important,” Wedeking said, “is that when people come into that clinic, they see a familiar face.”

These existing relationships with community health workers and local organizations are a key driver

behind the success of the Community Outreach Program. “Our community partners are the critical link to reach community members who are most at risk,” said Spector. “We need [them] as they know their communities best and have established the necessary trust.”

“Casey doesn’t go in and take over,” Brinks added. “We’re careful how we expend our resources, so we can respect the community clinics.”

Using new technology

The biggest technological advances for the program may go unrecognized by participants who come for screenings and glasses. But if all goes as planned, the new technology will make vision care faster and more efficient.

Oculomics — an emerging technology that combines high-resolution ocular imaging, big data and artificial intelligence — will make it easier to detect common eye diseases early, before the damage is irreversible.

OHSU is developing technology that will help create a huge database of retinal scans using optical coherence tomography, better known as OCT. Think of OCT as a CT scan for the eyes. An invisible beam captures thousands of high-resolution retinal images per second, which can be used to diagnose and monitor common eye diseases. OCT angiography, or OCTA, is a newer imaging technique that could help ophthalmologists find biomarkers of a broad range of diseases far beyond glaucoma and cataracts by giving them a better view of vascular circuitry and blood flow within the retina.

“It is imperative that we include these populations in our data to help build the artificial intelligence models.”

Michelle Hribar, Ph.D.

Ultimately, the OCT images will be de-identified — have any identifying information about patients removed — and stored in a database of retinal scans from patients who have already been diagnosed with other illnesses. Researchers are building artificial intelligence models that will compare those images to scans taken during routine eye exams. So, if a scan taken during a visit to the mobile clinic matches scans in the database from people with Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, coronary artery disease or stroke, providers could know that the patient in front of them is at risk for the same disease.

“It will allow the person in the clinic during the screening to immediately tell that patient, ‘Here’s what your next steps are,’ as opposed to having to call them two or three days later to say, ‘You need to follow up,’” said Michelle Hribar, Ph.D., assistant professor of medical informatics and clinical epidemiology in the OHSU School of Medicine. “It’s a lot easier to talk to them and counsel them in the moment at the clinic.”

Most of these scans are commonly captured at hospitals and eye clinics, which has resulted in a limited and somewhat homogenous sample of images. By gathering images at outreach sites, researchers will be able to build a bigger and more diverse database that better reflects Oregon’s communities. This expansive dataset will span the region’s many races, ages and incomes, as well as populations who often don’t have easy access to vision care.

“It is imperative that we include these populations in our data to help build the artificial intelligence models,” Hribar said.

For now, OHSU will provide the most advanced model of OCT imaging devices for vision care at eight telehealth sites in Oregon. But developing the necessary artificial intelligence and big data to diagnose a host of illnesses through retinal scans isn’t a pie-in-the-sky scenario. It won’t take decades to come to fruition. These advances will be here in a matter of years, and OHSU is at the forefront of their development.

Paving the road ahead

The new iteration of Casey Eye Institute Community Outreach Program is far different than what was envisioned in 2010. It’s bigger and more ambitious, with a team of researchers hard at work on new technology and new treatments. But the top priority hasn’t changed: preventing blindness by providing first-class eye care throughout the state. An extensive network of nonprofit community centers at nearly every crossroads in the state is eager to begin anew.

None of it would be possible without the generosity of philanthropists. From training Vision Health Navigators to maintaining the mobile clinics, it takes money and time to make expert vision care available in Oregon’s isolated communities. The expansion is achievable because of $4.15 million in gifts from the Roundhouse Foundation, Heather Killough, Rocky and Julie Dixon, S. Page Evans and the Theodore Rutherford Lilley Fund of the Oregon Community Foundation.

“Taking the time to build strong relationships,” Brinks said, “and working alongside real-world populations to build these programs means those dollars and that time will be well-spent, and many people’s lives will be the better for it.”

That’s because there is no data set or algorithm more important than the human touch to prevent blindness.