She came back to say thanks.

And to provide a living, walking testament to how miracles can happen. With a little help. A lot of faith. And whole lot of work.

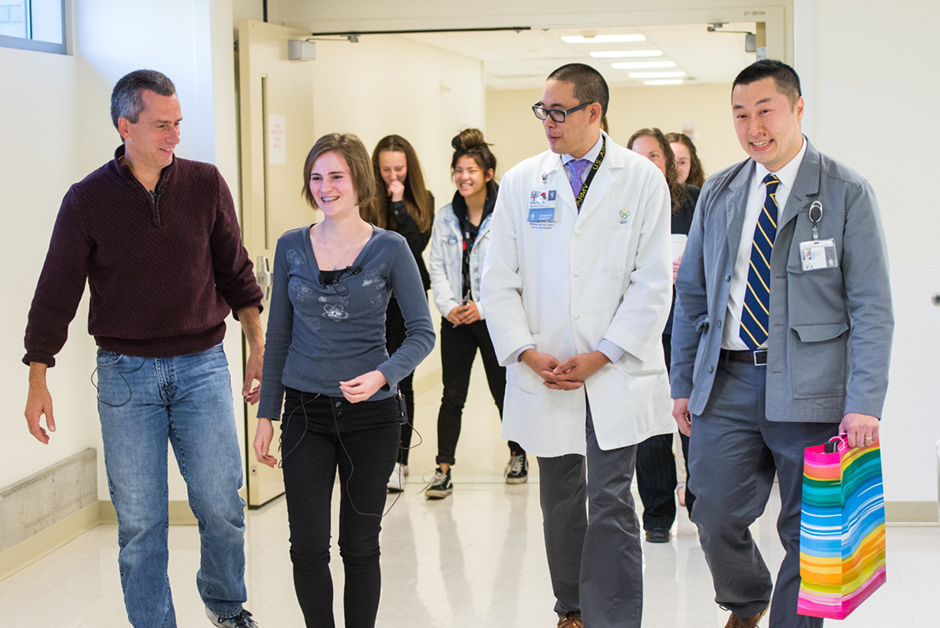

On a sunny October morning, one day short of a year after a horrible accident, Ana Wakefield and her family came back to OHSU to visit the neurosurgeon she had never really met before — the one who saved her life. And to say thanks to the entire team of OHSU surgeons, nurses and others who took care of her during her stay at OHSU.

“This was about us being able to meet Dr. Chang personally, face to face, and thank him,” Dave Wakefield said, standing next to his 21-year-old daughter, waiting near the Kohler Pavilion terrace to meet with Jason Chang, M.D., an OHSU neurosurgeon. “He was the biggest piece that helped Ana. Without his skills, she wouldn’t be alive.”

An early morning accident – and the rush to save a life

The accident happened in the early morning on Oct. 18, 2017, on a highway in Clackamas County. Ana Wakefield, a junior basketball player at Multnomah University, was driving to practice when a driver of a stolen vehicle crossed the center line and slammed head-on into her car. The driver ran from the scene. (A suspect was arrested nine months later, and is set to go on trial in February on second-degree assault, hit-and-run and other charges.) Ana was whisked to OHSU, gravely injured.

She had open fractures on both legs, a collapsed lung, a fractured eye socket and massive brain and other injuries.

Chang and an OHSU surgical team performed an operation to remove part of Ana’s skull to allow room for her swelling brain. He and his team would perform four more brain surgeries over the next three weeks.

Early on, it wasn’t at all clear whether Ana would survive. But during those first few days at OHSU, Dave remembers a discussion Chang had with him and Ana’s mother, Rachel.

“He said, ‘I can’t promise you anything. But I’ve done the best I can do,’” Dave Wakefield remembers. “He said: ‘Good things happen when you work hard.’ He told me all along that this would be a marathon, and if you really want to get her back, you have to work hard at it.”

“We need a Dr. Chang there for every Oregonian, at any time, in their moment of need.”

Nathan Selden, MD

After three months in the hospital, first at OHSU, then at Kaiser-Permanente Sunnyside Medical Center, Ana was transferred to the Legacy Rehabilitation Institute of Oregon at Portland’s Good Samaritan Medical Center.

At that point, Ana was in a wheelchair, couldn’t walk, and couldn’t talk. But she was ready to fight. She and her dad decided they were going to run that proverbial marathon. And run it very hard.

A long, hard recovery

Medicine doesn’t fully understand traumatic brain injury, and recovery can vary widely with injuries as severe as those Ana experienced. What has been shown, however, is that for patients who survive the first few weeks, intense rehabilitative therapy can significantly influence their recovery, especially during that first year.

The physical and cognitive therapy is an attempt to help the brain re-wire itself — to have it establish new brain patterns to work around the brain damage, allowing the patient to get back to as near normal as possible.

After a few weeks at the Rehabilitation Institute, Ana came home and worked on her physical and rehabilitative therapy from 7:30 a.m. to 4 p.m., six days per week. Her dad was at her side throughout, taking a year-long leave from his teaching job to support Ana in her recovery.

Ana knew she wanted to work as hard as humanly possible, to claw back as much of normal as she could. Her persistence became famous at her former high school, Damascus Christian School — even among students who never knew her. Students started wearing sweatshirts and bracelets with the phrase: “Fight like Ana.”

Now, more than a year after the accident, Ana knows how far she has come.

She speaks well. She walks — and runs — with a slight limp. She won’t be able to play college basketball again. But there’s a video of her online, back on the basketball court, shooting hoops. And making most of the shots.

Meanwhile, she’s been taking college classes online, and hopes to be back on the Multnomah University campus as a full-time student by January 2019.

Over the past few months, she’s spent several days a week at the Brain Injury Rehabilitation Center in Portland, where she’s been working on cognitive therapy to help her with short-term memory.

A next huge step both she and her parents want is for her to regain some of the independence she had in October 2017, as a 20-year-old college junior double majoring in Bible/Theology and Business Administration, working at the YMCA and volunteering in her church’s youth group. She still can’t drive and wants to get her license back. She still lives at home, but, with help from family members and others, her parents are building an accessory dwelling unit in their backyard for her to live in for a while.

“We joke — I want her out of my house,” Dave Wakefield says, smiling. “I want her to be independent. I want her living a life.”

“In an ideal situation, none of us would be babysat by our dad,” Ana says, also smiling.

“She has made amazing progress,” Dave said. “I know, statistically speaking, where she’s at and where she should be.”

Dave says Ana wouldn’t be alive if it weren’t for the expert work of Chang and the OHSU medical and surgical teams. And she wouldn’t be where she is without the advice that Chang gave the family a year ago.

“This is not the norm. And I’m giving Dr. Chang credit,” he said. “I can’t say enough good things about what OHSU and Dr. Chang have done.”

How philanthropy helps save lives

Nathan Selden, M.D., the Mario and Edith Campagna Chair of Pediatric Neurological Surgery at OHSU, says happy stories like Ana’s depend on OHSU having the technology and talent to offer the best care possible. And philanthropy has a lot to do with that.

“We need a Dr. Chang there for every Oregonian, at any time, in their moment of need,” said Selden, who recruited Chang from Washington University in St. Louis in 2015.

“Philanthropy is at the heart of making that happen. To bring the best and the brightest, equip them, retain them, and fund the research they do requires transformational philanthropy. That’s what we all do to make sure there is someone like Jason Chang there when we need them.”

Chang knows that the medical care Ana received after the accident was vital. He also knows how rare her recovery is and credits her progress to her fierce determination and commitment to therapy, and her family’s unwavering support.

He remembers the conversations he had with Ana’s parents right after the accident — about not giving up hope, about the marathon. And he remembers Dave telling him that, one year after the accident, they would come to the hospital to show him how well Ana was doing.

“Ana’s dad said, ‘You know what? Mark my word. Mark your calendar now. We’re going to come right through here and show you how much passion we have about this,’” Chang said. “It was true. It was like someone calling out that they’re going to hit a grand slam — and then doing it.”