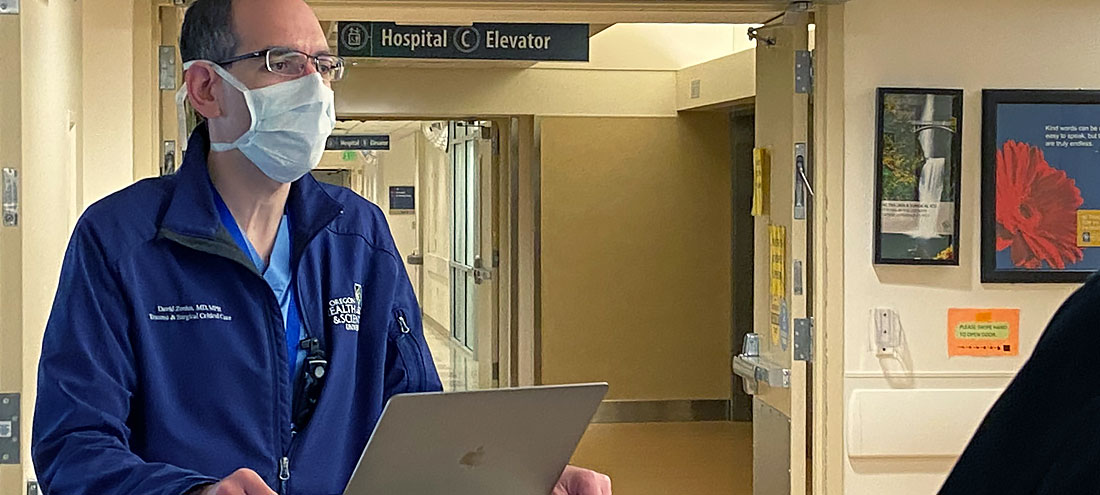

For David Zonies, MD, MPH, there’s never a dull moment — and he prefers it that way.

Zonies is a trauma surgeon in OHSU’s Division of Trauma, Critical Care and Acute Care Surgery, as well as the Director of Surgical Critical Care and the Extracorporal Life Support program at OHSU, a program he started when he joined OHSU about six years ago.

He has also been instrumental in developing and leading OHSU’s critical care surge plan: figuring out how the hospital would expand capacity during an increased demand for medical care caused by an emergency or a pandemic like COVID-19.

It’s an intense group of responsibilities, in which he and his colleagues must make complex decisions with little time to waste.

With COVID-19 accelerating the shortage of essential medical tools, Zonies and his colleagues needed to prioritize accordingly to avoid a worst-case scenario: People dying because of a lack of lifesaving equipment. So they fast-tracked several initiatives to ensure no one would lack access to critical health care.

Developing a plan

Even without a pandemic going on, ventilators are a scarce resource and extracorporeal life support machines even scarcer. Months ago, when Zonies and his team learned what was happening in China, Italy and throughout Western Europe, they realized the potential impact of that scarcity.

Extracorporeal life support, also known as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), is a potentially lifesaving procedure to help a critically ill person’s heart and/or lungs. It is the next step when a ventilator cannot provide a patient with enough oxygen. Both of these machines are crucial in the fight against COVID-19.

Ventilator and ECMO machine parts are typically made in Asia and Europe — but the spread of COVID-19 across the globe halted production. That meant OHSU had to be creative and develop new systems to acquire and manage ECMO equipment to ensure access to this lifesaving equipment for the patients who need it most.

“ECMO is a scarce resource, but now we can be consistent with who we offer it to, in an ethical and equitable manner.”

OHSU and Zonies took the lead for the region in assessing ECMO capability throughout the Pacific Northwest, developing equitable, safe protocols on when to use ventilators and ECMO, so no provider would be in the position of rationing lifesaving resources. There are only about 10 medical centers in the region where people can receive ECMO. But by working together, maxed out hospitals can transfer patients to other hospitals that have room.

Each week, Zonies conducts calls with all 10 of the ECMO centers in Oregon and Washington to discuss ECMO capacity. They have also created a website and dashboard featuring real-time updates detailing ECMO availability across the area — ensuring patients are able to receive the care they need while remaining as close as possible to home.

“ECMO is a scare resource, but now we can be consistent with who we offer it to, in an ethical and equitable manner. The process will be the same, no matter whether you’re in Portland, Seattle, Spokane or Tacoma,” he said.

“Thankfully, because people in the Pacific Northwest are generally socially responsible and are adhering to stay-home measures, we haven’t needed to implement the crisis plans we’ve developed,” Zonies continued. “But if we see future waves of COVID-19, or a disaster like an earthquake, we now have these measures in place.”

“Doc in the Box”

A crisis has a way of making postponed projects a priority. In addition to establishing protocols around ECMO, Zonies cites another positive development that has come out of COVID-19 preparedness: a virtual ICU.

Before COVID-19, OHSU had been working on deploying a virtual ICU to support other hospitals, in which providers use remote video technologies called telemedicine to care for patients. Within a few weeks, OHSU deployed the virtual ICU internally.

Telemedicine ICU doctors are located in a command center on the OHSU campus. They can provide oversight and expertise to non-ICU physicians and nurses at outlying hospitals where there’s a critical shortage. They communicate via a robot or through the use of “smart” tablets that have secure audio-visual capability. Providers can also use a form of artificial intelligence (AI) technology to receive an early warning about patients whose condition may be worsening.

“We have partners all over Oregon and Washington who can’t bring in additional ICU doctors, but need help. Now we are poised to support them.”

Virtual ICUs don’t replace traditional bedside ICU coverage, but they can provide another layer of support for both patients and providers. Even a patient on ECMO would be able to use the telemedicine platform. Also, in an event like COVID-19, telehealth can reduce health care workers’ potential exposure to the virus.

“We care for the sickest of the sick,” Zonies said. “That also means the highest chance of exposure to the virus, and of high levels of the virus. We need to take every possible precaution to contain and mitigate that risk.”

OHSU has made changes to all its adult ICU beds to allow for telemedicine capability. In addition, because OHSU postponed non-urgent procedures, staff used this opportunity to wire currently empty units for telemedicine, which can be used now or in future crises.

“This was a three-year plan that turned into a three-week effort,” Zonies said. “Our virtual ICU expands our ability to cover other ICUs, providing a ‘Doc in the Box’ to multiple patients. We have partners all over Oregon and Washington who can’t bring in additional ICU doctors, but need help. Now we are poised to support them.”

Working together to flatten the curve

OHSU’s surge plan covers what to do in case of a dramatic and fast increase in the number of people seeking care at the hospital who have COVID-19.

The plan includes how many potential hospital beds OHSU could maintain, ways providers could be redeployed to provide critical care services and any potential re-training that would be needed, and what would be required to convert various hospital units into COVID-19 units. Zonies also collaborated with OHSU Health System partners such as Tuality and Adventist to expand critical care beyond Marquam Hill. For example, although their ICUs are smaller, OHSU could supply providers to expand their manpower.

As a military officer and a colonel in the U.S. Air Force Reserves, Zonies is familiar with crisis planning and disaster management strategies. But he stresses that good planning doesn’t happen in a vacuum: There’s no substitute for joining forces with others.

“Everyone doesn’t have to be independently figuring this out. Partners can help come up with a plan. It’s not always about OHSU pushing out what to do. We want to incorporate good ideas from everybody.”

What keeps him going

COVID-19 is a new disease, but preparing for the unexpected is nothing new to Zonies.

“The next disaster might not be a viral pandemic. I’m a trauma surgeon and involved in disaster work, and we live in a disaster zone: the Cascadia Subduction Zone, with its major earthquake risk. Hopefully now people will better understand what it means to be prepared.”

At work, he’s witnessing a renewed commitment to OHSU’s mission of providing the best possible health care and has been impressed by every employee he’s worked with, from administration to support staff to frontline workers.

“It’s not just health care, but the health of people.”

He also feels he has a great responsibility for his colleagues and making sure they’re safe.

“We are asking them to do heroic things and stand in harm’s way. So we need to help them, have their backs, and trust that without them, the system breaks down,” he said.

He’s hopeful that Oregon has outperformed predictions and is actively working on flattening the curve by staying home. Zonies hopes that another unexpected benefit will be knowledge of and support for public health.

“It’s not just health care, but the health of people,” he said.