As the COVID-19 pandemic spread across the globe, health care workers worried they would run out of ventilators needed to keep the sickest patients alive. That’s when Albert Chi, MD, MSE, an OHSU trauma surgeon, sprang into action.

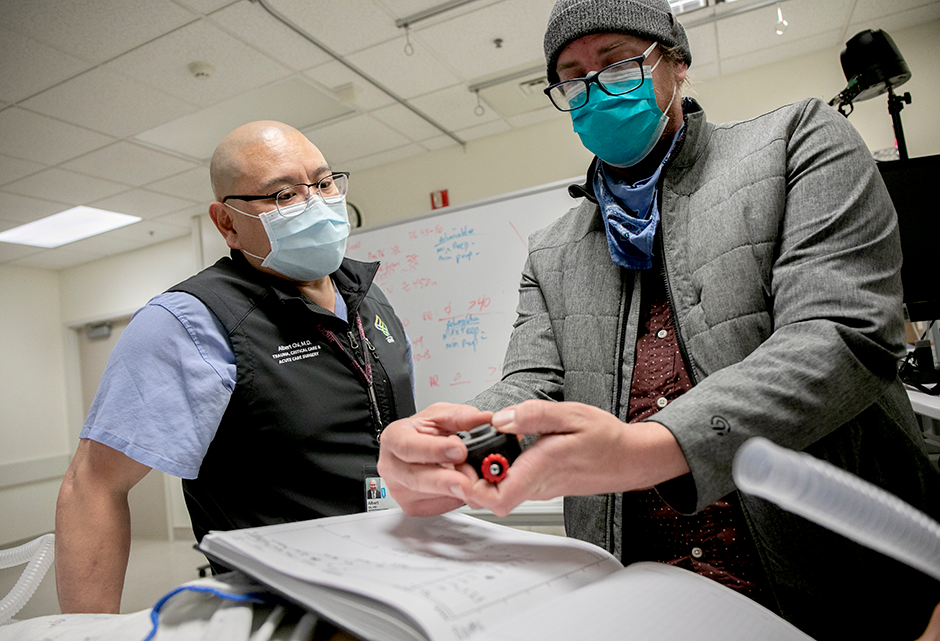

At the first signs of an impending ventilator crisis, Chi pivoted his lab — which previously pioneered 3D-printed prosthetics for children — into developing a low-cost ventilator solution. The result is astonishing in its simplicity, accessibility and effectiveness. For less than $10 in materials, the crisis ventilator can be produced in a matter of hours using an industrial-quality 3D printer and components that are readily available at any hardware store.

The simple mechanical design has no specialized parts, sidestepping the supply chain problems that can slow delivery of ventilators from manufacturing plants to hospitals. The design is unique in providing the ability to conjure new ventilators in place for any hospital that can access a printer.

The ventilator could be a game changer for areas hardest hit by the COVID-19 virus. This week, Chi and his team filed for emergency use authorization from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to speed the deployment of the design across the country.

Imitation lungs, real progress

Chi and his core team, lab research engineers Whitney Menzel and Evan Fontaine along with Stephanie Nonas, MD, director of the medical intensive care unit at OHSU, and Dennis Child, an OHSU respiratory therapist, began working on the design nearly four weeks ago — all in their homes due to physical distancing measures.

They wasted no time. The team worked around the clock to design, build and test a product that would have taken several months to develop in normal circumstances.

“It was complete excitement. It seemed as though our lab was made to do this,” said Chi. “To think outside of the box and to come up with a solution, my team was completely excited for the challenge.”

With initial prototypes, the team used small, balloon-like imitation lungs to test how the ventilator performed. After some modifications, they moved their testing to OHSU’s simulation lab to compare their design to a standard ventilator, using a mechanical training lung that can simulate the disease processes of COVID-19.

“We needed to know this ventilator will work on a diseased lung,” said Chi.

They repeated this process of testing, refinement and re-testing with help from the 3D printing technology firm Stratasys and the nonprofit organization Limbitless Solutions who partnered to print high-quality prototypes. The team also got an assist from Nike who helped by 3D printing the team’s design.

“It’s one thing to build it in a lab, but another thing to have a quality print that’s reliable so that you’re able to put it on a patient,” said Chi. “That’s where our partners at Nike and Stratasys came in. They enabled us to do robust materials testing.”

In just a few short weeks, the team arrived at a design that worked. In fact, tests on simulated lungs show it works as well as a conventional, standard-of-care ventilator.

The unit is purely mechanical, with no electronic parts. It runs on the standard oxygen supply available at hospitals and clinics worldwide — eliminating the need for electricity. It can be manufactured within three to eight hours, depending on the printer.

Chi and his team did not sacrifice sophistication for simplicity. Compared to many emergency ventilator devices currently being developed, the ventilator can not only do basic ventilation, but also has more advanced ventilation modes for the sickest patients.

No patient who has a chance to survive with ventilation should die for lack of available equipment. If the design is approved by the FDA, clinicians around the world could be spared the heartbreaking burden of making life-or-death decisions forced by ventilator shortages.

Chi’s research and work wouldn’t have been possible without the generosity of donors. Philanthropic support for Chi’s lab has purchased equipment and materials and funded staff who are essential to this work. This support comes from many individual donors and from Fastpitch Cares, a local nonprofit organization.

For a better future

Long term, the design could be useful in future pandemics. Chi, formerly an officer in the U.S. Navy Reserve, also envisions the possibility of using the device as a “pocket vent” in military operations or in other austere environments with limited access to electricity — such as the scene of a natural disaster.

While rates of infection in Oregon and some parts of the United States appear to be flattening due to stay-at-home orders and other physical distancing measures, the virus continues to spread in other parts of the world. These ventilators may yet be necessary to manage secondary surges in Oregon and other hot spots that flare up across the U.S.

“This project had a greater scope and impact than just the state of Oregon — our goal was to impact the nation, even the world.”

“We’re not out of the woods yet,” said Chi.

Once the ventilator is approved by the FDA, Chi will begin reaching out to areas hardest hit by the virus and offer the 3D printing design to medical communities that need it. His team will also continue to test and refine the prototypes.

“Our response as a community has been incredible,” said Chi. “This project had a greater scope and impact than just the state of Oregon — our goal was to impact the nation, even the world.”