“If I do all that I hope to do, I shall probably make some inventions.” So wrote M. J. “Jack” Murdock in 1934 at age 16. Two years later, just as predicted, the teenage technophile started his own radio business that, years later, would lead to the founding of the business that would set the standard for technological innovation in Oregon: Tektronix.

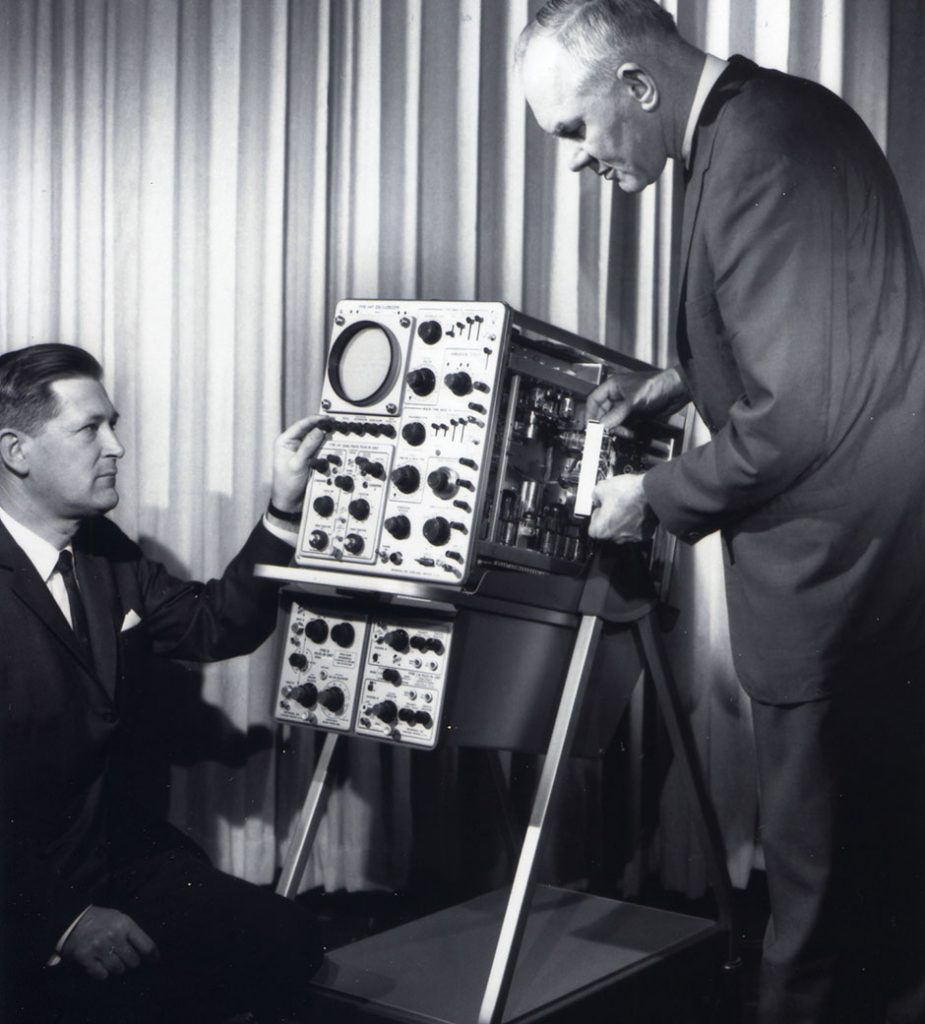

Co-founder Howard Vollum led the company’s research and development efforts, but Murdock was every bit as much of an inventor. What Vollum was to signals and circuits, Murdock was to people and their passions. As the engineer of what became known as “Tek culture,” Murdock cultivated an egalitarian, people-focused working environment that became the model for high-tech companies everywhere. Murdock became an inventor of inventors – generations of them.

He remains a force for discovery, education and human enrichment long after his untimely death in 1971, thanks to the M.J. Murdock Charitable Trust’s stewardship of his legacy. On the centennial of Murdock’s birth on August 15, 1917, there’s no better time to look back on this extraordinary life and its ongoing impacts across the Pacific Northwest.

Early days

Jack Murdock’s story could have been lifted from the pages of The Greatest Generation. Born to a working-class family in southeast Portland, Murdock grew up amid the tumultuous events of the early 20th century. It was a time of world war and widespread poverty, yet also one of unfettered scientific and technological innovation.

As he came of age, wartime advances in aviation, manufacturing, transportation and communications were rapidly transforming every aspect of American life.

Larger-than-life figures of science and industry like Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, Albert Einstein and Charles Lindbergh were in the public eye and, like many kids of the era, Murdock was fascinated by their achievements.

The new phenomenon of broadcast radio appeared in Portland in the mid-1920s, and he caught the bug. By his account, he spent long hours building or fixing radios at his makeshift electronics workbench and, whenever possible, haunting area radio stations and supply stores for a glimpse at the latest professional gear.

After graduation from Franklin High School, his father offered him a fateful choice: a subsidized college education or an equivalent amount of money with which to start his own radio/TV-related business. He chose the latter, establishing an appliance dealership on Southeast Foster Road. The seeds of Tektronix were sown soon after, when Murdock joined forces with Howard Vollum, a Reed College physics graduate who transformed the dealership’s repair shop into their private research and development lab.

Larger-than-life figures of science and industry like Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, Albert Einstein and Charles Lindbergh were in the public eye and, like many kids of the era, Murdock was fascinated by their achievements.

By 1947, after serving the U.S. Coast Guard during World War II, Murdock had assembled a core team of trusted colleagues, incorporated the business and sold Tektronix’s very first product – a portable oscilloscope – to the University of Oregon Medical School, known today as OHSU. Tektronix’s improved oscilloscopes revolutionized the electronics industry and gave rise to the modern computer. Before long, Tektronix was Oregon’s largest employer, the source of nearly 200 corporate spin-offs and a model of corporate responsibility.

Tek culture and the rise of Oregon Graduate Center

Murdock was, by all accounts, universally liked and respected. He was said to be a man of few words and a reluctant public speaker, but a highly astute listener. In the radio dealership days, his attentive ear and natural charm converted more than one unhappy customer into a repeat buyer. Later at Tektronix, Murdock went to lengths to get to know employees on a personal level, learning about their families, their interests and details of their jobs.

As the workforce grew too large to maintain that level of connection, Murdock feared employees might lose sight of the company’s core values. So arose the fabled Tek culture, and a set of progressive-for-the-times human resources practices that Murdock designed to leverage the full power of Tektronix’s human capital.

An investment in education and professional development was a cornerstone. To Murdock, who was deeply interested in human psychology, the pursuit of knowledge was a fundamental requirement for human happiness, and he believed happy employees performed better.

Yet the Portland area had no major university providing graduate-level education in science and technology in those days. On his watch, the company launched the Tektronix Education Program, later informally known as Tektronix University, a comprehensive in-house training and professional development program.

Nevertheless, at the 1950s peak of the Cold War and the dawn of the Space Age, the region’s need for a scientifically literate workforce went beyond what any one company could meet – it became a matter of national security. Murdock and Vollum were part of an informal think tank of regional corporate leaders concerned about their competitiveness in this uncertain new world.

With the support of then-Governor Mark O. Hatfield, group members pooled their money and political clout to persuade the Oregon Legislature to charter the Oregon Graduate Center for Study and Research in 1963. OGC, later renamed the Oregon Graduate Institute of Science & Technology, became the Portland area’s first graduate education and research institute, with programs in physics, chemistry and materials science.

Tektronix’s generous donations – including the building that served as its first campus – helped the nontraditional school weather the challenges of its start-up phase. Over the years, the company’s pro-education policies enabled hundreds of Tektronix employees to integrate graduate-level study and research at OGC into their regular jobs.

An investment in education and professional development was a cornerstone. To Murdock, who was deeply interested in human psychology, the pursuit of knowledge was a fundamental requirement for human happiness, and he believed happy employees performed better.

Just as Jack Murdock believed employees in the automation age must be prepared to adapt to the times, OGC itself reconfigured and restructured many times to meet local companies’ changing needs. With the advent of the laser in the mid-1960s, the school became nationally known for its expertise in advanced optical measurement techniques.

In the 1970s, it established one of the nation’s first departments of environmental science and engineering, led by internationally respected experts in atmospheric and aquatic chemistry. OGC electrical engineers under the leadership of Dr. Lyn Swanson, started up FEI to market a novel semiconductor manufacturing technology called focused ion-beam technology.

And in the early 1980s, Oregon’s first graduate-level program in computer science and engineering was established and quickly became the institute’s largest department. Tektronix Foundation support and personal gifts from the company’s founders made much of it possible.

Ongoing impact through philanthropy

As Tektronix went through its own restructuring and refocusing, Murdock began to devote more of his time to side projects in aviation, horticulture, leadership development and other personal interests. Sadly, before he had the chance to witness the impact of Tektronix’s support on the graduate institute, he lost his life in a floatplane accident in 1971 – the same year OGC awarded its first graduate degree.

A bachelor with no close relatives surviving him, Murdock invested the bulk of his estate to form the M.J. Murdock Charitable Trust, based in Vancouver, Washington, whose first three trustees were his close friends Jim Castles, Paul Boley and Walt Dyke. With thoughtful attention to Murdock’s personal values and philanthropic interests, the trust today awards millions of dollars to educational, human services and cultural organizations in Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Alaska and Montana.

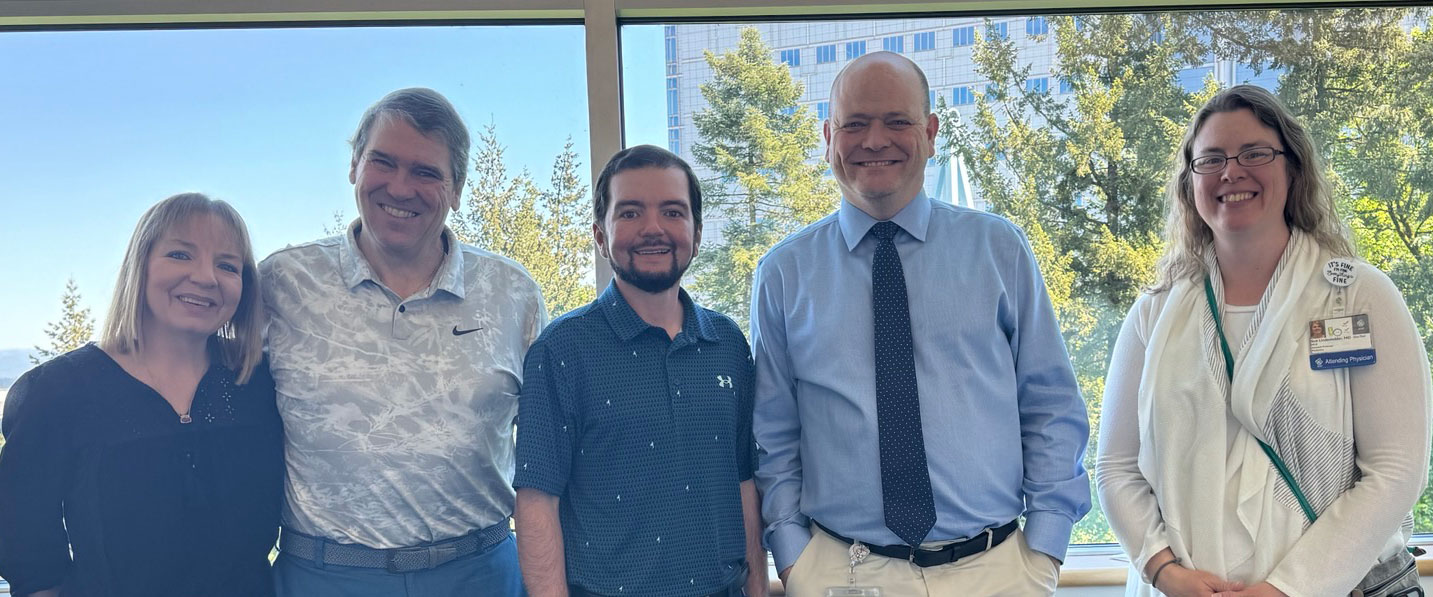

At OHSU, Murdock Trust grants totaling more than $34 million have supported the acquisition of state-of-the-art research equipment, the education and training of promising graduate scientists, and the discovery of critical new knowledge about human health and disease.

Perhaps the most symbolic of the M.J. Murdock Charitable Trust’s many investments in OHSU was a $4 million grant establishing Oregon’s first graduate program in biomedical engineering at the Oregon Graduate Institute, thereby paving the way for the historic 2001 merger with OHSU.

Today the OGC/OGI tradition lives on in OHSU’s Department of Biomedical Engineering, a nationally respected innovator at the interface of health care and technology. Substantial recent support from the Trust has provided OHSU’s labs with state-of-the-art imaging and computing technology central to our efforts to defeat cancer through earlier, more precise detection.

At OHSU, Murdock Trust grants totaling more than $34 million have supported the acquisition of state-of-the-art research equipment, the education and training of promising graduate scientists, and the discovery of critical new knowledge about human health and disease.

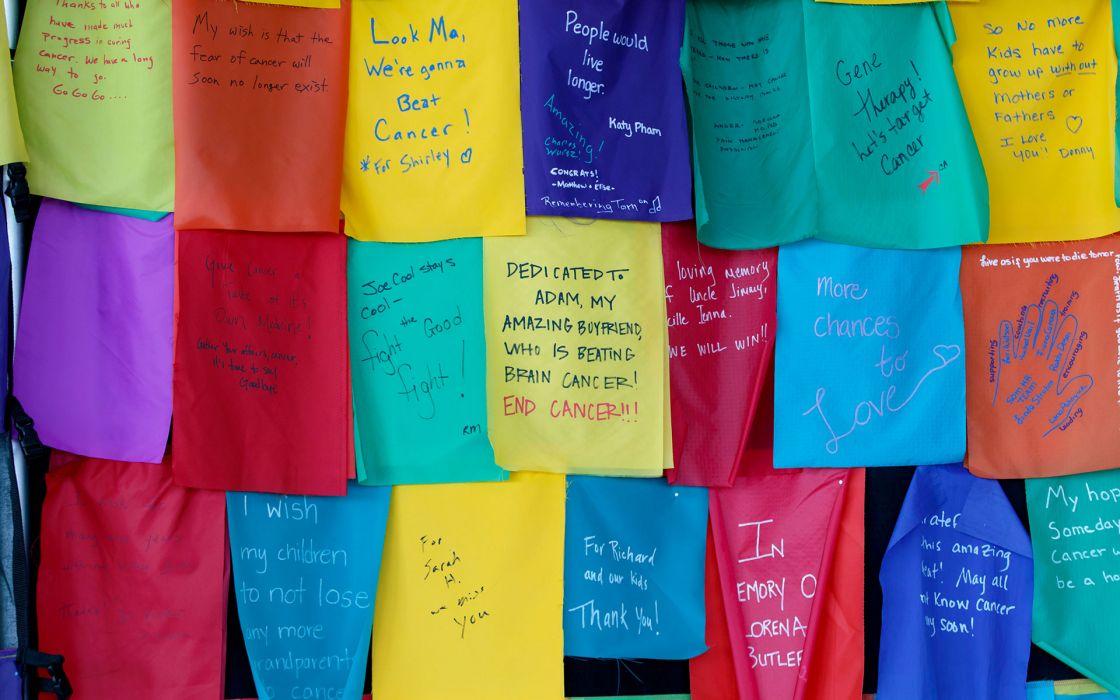

The advanced tools of discovery, such as nanotechnology, computational biology, multiscale imaging and advanced materials, will be critical in the future as scientists and engineers seek new ways to confront growing threats across the spectrum of human health. OHSU’s ability to adapt to this exciting new environment stems from the Trust’s exceptional support. The Trust’s ongoing support for more than 25 years of the Murdock Scholars program involves students from all the region’s top private universities.

Murdock’s body was never recovered after his tragic accident. But thanks to his unique genius, the wealth it generated during his lifetime and the integrity and stewardship of those to whom he entrusted it after his death, his legacy is in plain sight throughout the Pacific Northwest and beyond.