Humanity has spent millennia unlocking cancer’s secrets — learning its processes, how to treat it, live with it, cure it. OHSU is leading us into a new age of understanding a disease that has afflicted humans from the very beginning

By Josh Friesen

For Ignite Magazine

Of all the questions Flavio Rocha’s patients ask, there’s one that vexes him the most. One that keeps him up at night. One he’s spent a career in surgical oncology trying to answer.

“Did you get all of it?”

“Patients always have that question as soon as they wake up from surgery,” he says. “In my mind, it’s always, ‘Yes, I got all the cancer I can see and feel,’ but I know in several cases, there’s going to be microscopic disease. As a surgeon, I can’t remove every single cell of cancer; I have to rely on other therapies to do that job. So, how do we get to the point when I can say, ‘Yes, we got all your cancer, and we’re going to prevent it from coming back’? There are lots of encouraging things on the forefront.”

Rocha is physician-in-chief of the OHSU Knight Cancer Institute, the Hugh Hedinger and Georgeina Hedinger Chair of Surgical Oncology and division head of surgical oncology in the OHSU School of Medicine. A surgical oncologist who specializes in treating liver, pancreatic and biliary cancers, Rocha believes in leveraging everything at his disposal at OHSU in the holistic treatment of his patients.

The Knight Cancer Institute boasts an extensive cancer-fighting repertoire and is world-renowned for its innovative approaches in early detection, clinical trial research and outreach, and immunotherapy treatments. Gleevec, a revolutionary cancer drug primarily developed at OHSU and approved by the FDA in 2001, paved the way for the institute’s continued leadership in the field of precision oncology. The institute is also identifying and solving for how to address gaps of inequity that disproportionately affect underserved and underrepresented populations.

And when the ribbon is cut on the new, 14-floor inpatient addition to the OHSU Hospital in the spring of 2026, OHSU will further expand its ability to provide complex cancer treatment — the impact of which will reverberate throughout Portland, Oregon and the entire Pacific Northwest.

“If we can turn cancer into a manageable, chronic disease, we’ll be able to achieve what we ultimately want, which is reducing cancer death and morbidity.”

Flavio Rocha

“It’s exciting to see the science behind what we do,” Rocha said. “We’ve learned so much. We’ve made tremendous progress. There are also things that remain unsolved. The more we boost our research into cancer biology and cancer treatment, the more we can serve all populations in need. That’s where I see us in the future.”

Our triumphs of yesterday signal a bright tomorrow. Scientific breakthroughs are leading to more individualized, holistic treatment strategies that span a patient’s entire health journey, and the Knight Cancer Institute’s vision of a world freed from the burden of cancer is perhaps more attainable than ever. But forecasting the reasons for hope on the horizon requires a deeper understanding of the past — a tale of discovery almost as old as humanity itself.

A chaotic, ancient disease

The number of cell divisions a person experiences each day is comparable to the number of galaxies in the known universe — the exact figure resides somewhere in the neighborhood of the hundreds of billions. Each division is a virtually imperceptible yet essential building block, a biological function critical in the growth and maintenance of the complex, organic machines we call our bodies.

Those cells are packed with DNA, and every time a cell splits, it copies its genetic code over to its daughter cell. But DNA replication, unsurprisingly, is no walk in the park, and mistakes are common. Fortunately, our bodies come equipped with sophisticated detection and repair processes that catch and correct the vast majority of those errors almost instantaneously.

Some errors, however, can slip past the checks and balances.

“If this new cell acquires a mutation that unhooks the brakes for division, then that cell will become cancerous,” Rocha said. “This is what we call an oncogene. When an oncogene gets activated, it does what it knows best: starts dividing. That, at a molecular level, is what’s happening. That’s cancer.”

Despite cancer’s complexity, its underlying molecular mechanisms have stayed the same — even over the course of millennia. In 2016, a team of scientists discovered evidence of osteosarcoma in pieces of foot bone and spine from a pair of hominin samples 1.7 and 2 million years old, respectively. When tested against a modern osteosarcoma specimen, the cancers looked identical.

The takeaway? Cancer isn’t the modern malady we once thought it was. Cancer, it seems, is a natural byproduct of multicellular life, a phenomenon that emerged right alongside us humans. Unearthing its biological and historical roots lends important context that influences how researchers develop treatments and prevention strategies.

“There’s been a huge evolution in how we diagnose and manage cancer,” Rocha said. “Chemotherapy, radiotherapy — those were the earliest tools we had. But now as we move on to a more molecular age, we’re really learning more about the DNA of cancer.”

End cancer as we know it

If cancer is an inherent genetic process, can it truly be cured? Researchers are still searching for an answer.

But can cancer be controlled? Managed? Molded into a treatable, chronic disease? We’re already well on our way to achieving that goal.

According to the American Cancer Society, cancer mortality has decreased by 33% nationwide since 1991. Our tools are better at finding early signs of cancer, enabling doctors to provide lifesaving treatments sooner. Immunotherapies boost and modify the body’s immune system to better recognize and attack cancer cells. One immunotherapy, CAR T-cell treatment, the FDA approval of which was secured thanks in part to the Knight Cancer Institute’s role as a major clinical trials site, has revolutionized care for children with leukemia and adults with hard-to-treat blood cancers.

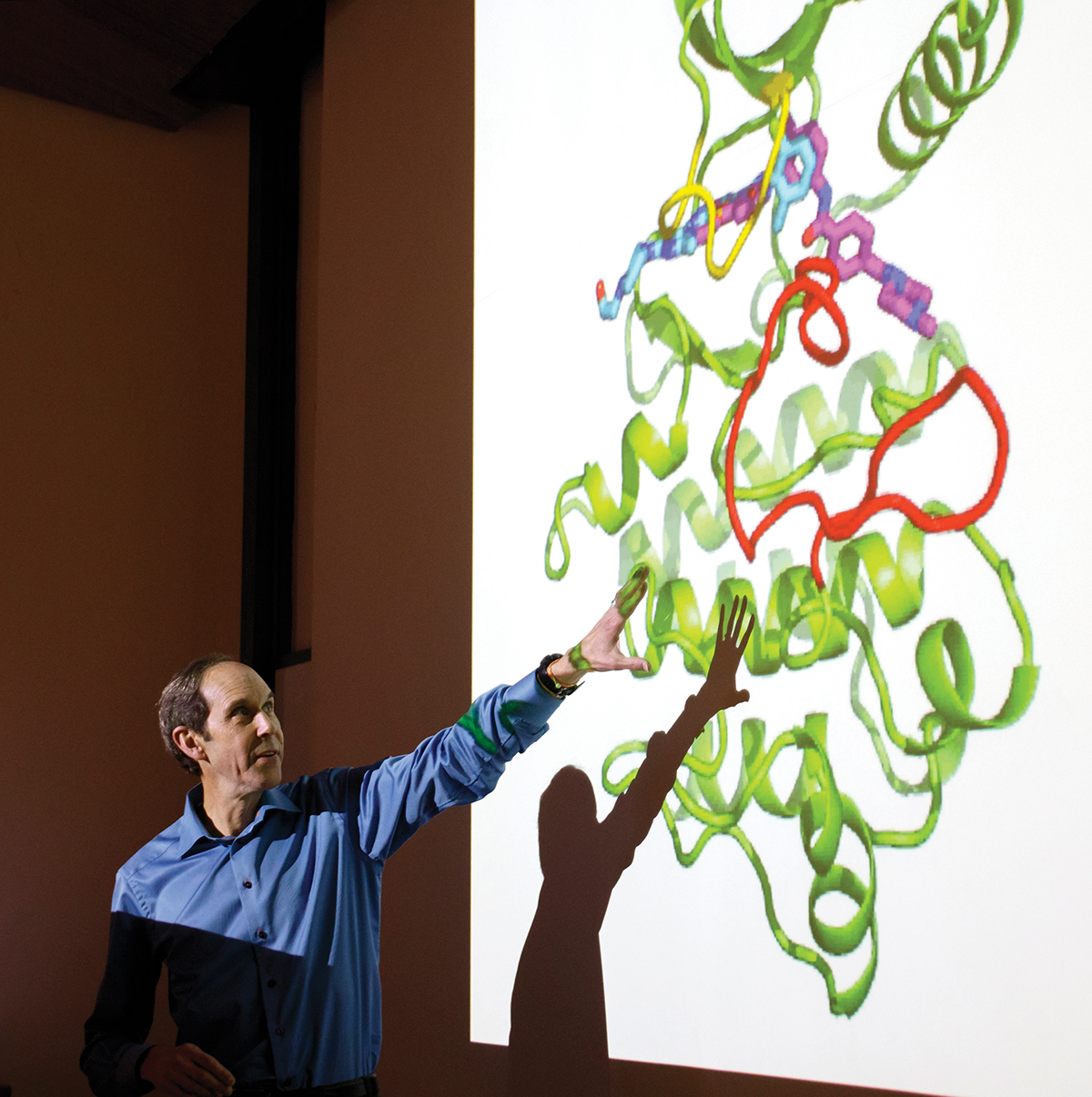

The advent of the landmark drug Gleevec, developed by Brian Druker, M.D., JELD-WEN Chair of Leukemia Research at OHSU, turned a once-lethal form of leukemia into a manageable disease. Gleevec was the first medicine designed not to kill cancer cells outright, but rather to fix the genetic coding error behind their frenzied growth. Precision oncology — the field that emerged from Gleevec’s development — is the targeted treatment based on the unique DNA profile of a patient’s tumor, allowing oncologists to home in on a cancer’s molecular signature and tailor-make more effective and less toxic treatments.

“Learning more about cancer allows us to do two things,” Rocha said. “One, find precision treatments that will knock out certain cancers, and two, minimize toxicity of treatment. If we can turn cancer into a manageable, chronic disease, we’ll be able to achieve what we ultimately want, which is reducing cancer death and morbidity.”

The path ahead isn’t without obstacles. Cancer disproportionately harms some populations more than others. Financial, geographical, environmental and racial factors all influence who is affected the most. Black populations suffer higher cancer mortality rates than all other populations for many types of cancers. Cancer patients in lower income brackets receive less treatment than their wealthier counterparts. Individuals living in rural areas, including in Oregon, are more likely to be diagnosed with and succumb to cancer and less likely to be involved in prescreening or clinical trials.

And recently, researchers have noticed cancer impacting younger generations more, a trend Rocha is currently studying.

“This is a disturbing trend we’re seeing nationally: younger and younger people presenting with early-onset cancer, which is between the ages of 18 to 49,” he said. “We haven’t been able to pinpoint exactly what the cause is, but it has triggered us to be more proactive about screening a population that typically was not eligible for screening.”

Between efforts to make cancer clinical trials more inclusive, collaborations like the Healthy Oregon Project and the Knight Cancer Institute’s Community Partnership Program, and outreach initiatives such as the institute’s mobile outreach van, OHSU is striving to narrow the systemic gaps behind these inequities.

“This is a big movement not just here, but nationwide,” Rocha said. “These are all things we as an institution [need to address], especially at OHSU, whose primary mission is to serve the people of Oregon and the surrounding area. That’s the way we see our mission.”

‘I am tremendously excited’

New treatments. New scientific fields. New understandings. The Knight Cancer Institute has made a habit out of changing the narrative of — and approach to — cancer.

Next on its to-do list of groundbreaking innovations: rebuilding cancer care from the ground up. The institute’s brightest minds are leveraging everything they’ve learned to improve cancer care from a patient’s initial visit all the way through to survivorship.

The upcoming inpatient addition, part of the OHSU Hospital Expansion Project, is a major step toward realizing that goal.

“I’m tremendously excited about this,” Rocha said. “The inpatient addition is going to give us the opportunity to have more patients treated and will give us the flexibility to accommodate patients in a new space that’s designed with collaboration and integration in mind.”

The 14-story, 513,000-square-foot inpatient addition will eventually increase OHSU’s total bed count by nearly one-third. Nestled on Marquam Hill alongside the main OHSU Hospital, the Kohler Pavilion and OHSU Doernbecher Children’s Hospital, the new building will be a bustling hub of interdisciplinary care. For Rocha and his colleagues, that means more access to innovative cancer therapies, surgical treatments and clinical trials.

“The building’s going to allow us to better coordinate our patient care and bring all our specialists to one place,” he said. “If you need a radiologist, a pathologist, a specialty surgeon, they’ll come to that building and see you.”

OHSU’s upcoming inpatient addition is the latest in humanity’s long and winding cancer journey. Our eternal quest to understand cancer, to reveal the molecular truths from beneath its enigmatic shroud, has brought us to this moment. Each new century, year, month and day is another step forward into a new era of cancer.

“If cancer is just part of being human, the question becomes, ‘Can we control it? Can we make it less lethal? If we can’t cure it, can we manage it?’” Rocha said. “I think, absolutely, yes.”