ADHD is so much more than a kid squirming at his desk. That’s still the public perception of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: just a bit of inattentiveness and fidgeting. Easily solved with medication.

Joel Nigg, PhD, an OHSU professor of psychiatry and one of the world’s top ADHD researchers, knows better.

This is what ADHD too often leads to, according to Nigg: Depression. Drug addiction. Mental illness. Homelessness. Shortened life spans. Suicide.

And often sidetracked lives — because no one understood what was happening in a child.

“However,” Nigg said, “the many new discoveries happening now make this an exciting and hopeful time.”

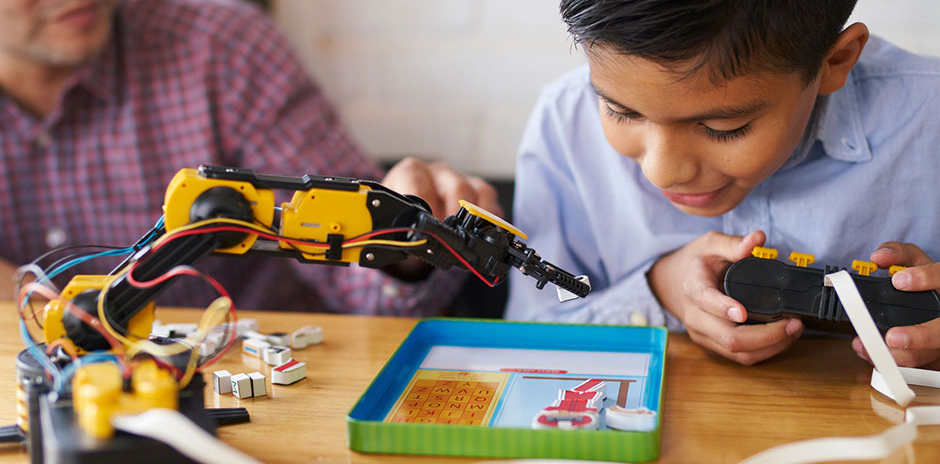

ADHD is one of the most common childhood mental disorders, affecting up to 11 percent of school-aged children. It’s characterized by unusual levels of inattention, impulsivity or hyperactivity. Children with ADHD often find it difficult to focus on a task, to sit still when needed, or to get along with others.

ADHD is typically the first mental health issue to emerge in young children, Nigg said. Diagnosis and treatment can help. But even then, ADHD often leads to problems that derail — and put at risk — children’s lives as they become adolescents and adults.

Adults with ADHD often have difficulties at their jobs, and in their personal and family relationships. Often, they have unrelenting feelings of frustration, anger or guilt. Very often, children and adults with ADHD develop other mental health issues.

Through their Abracadabra Foundation, Steven and Patricia Sharp have agreed to commit $12.5 million to fund a matching campaign for OHSU’s new Center for ADHD Research.

“ADHD doubles the risk of depression,” Nigg said. “ADHD doubles or triples the risk of addiction, depending on the drug. For adults with ADHD, it quadruples the risk of early death — from accident, suicide or illness.”

“Once you break it down, you realize — wait a minute, ADHD is a really big part of many problems we are grappling with as a society,” Nigg said. “ADHD is like a gateway.”

Nigg has spent 20 years trying to understand and change that. He’s now getting a whole lot of help.

In June, OHSU established the Center for ADHD Research, which Nigg will lead. It also announced that Steven and Patricia Sharp, through their Abracadabra Foundation, have agreed to commit $12.5 million to fund a matching campaign. The aim is to raise up to $25 million for the center to accelerate the team’s successful and innovative research.

The center’s goal will match what Nigg has been working toward for two decades: to understand different causes and influences for ADHD, find ways to detect it better and earlier, and then develop more effective treatments.

Nigg is director of the Division of Psychology within OHSU’s Department of Psychiatry, and a professor of psychiatry, pediatrics and behavioral neuroscience at OHSU. He was recruited to OHSU 11 years ago from Michigan State University to build OHSU’s ADHD program into one that’s nationally recognized. He’s done that, as he now works with more than a half dozen OHSU colleagues who have their own national scientific reputations.

“It’s one of the best groups of researchers studying ADHD in the country, if not the world,” Nigg said.

The team’s efforts focus on three primary areas. They work to better understand and differentiate the many types of ADHD through cognitive and other assessments of children who have it. They also are searching for possible biological “markers” of the condition or of treatment response — a way to see in a child’s blood, brain imaging or other biological characteristics something that correlates with ADHD, explains what’s wrong or identifies a best treatment. This includes team members’ pioneering efforts in brain imaging and genetics. Finally, they are beginning to understand how health and environmental factors affect a child or a child’s mother — even before a child is born — to create a risk of ADHD.

All three paths lead in the same direction: toward better ways to explain, detect and treat ADHD — and perhaps even prevent it from emerging.

For Nigg, it’s a matter not only of biology but also of family and society. After earning his bachelor’s degree from Harvard, he spent four years in inner-city Detroit, first working with homeless former psychiatric patients and then at a youth center for children and teenagers. He then worked for four years as a social worker in an inpatient psychiatry unit, seeing the devastation of mental illness and studying patients’ early life histories. He grew to understand how social, psychological, developmental and behavioral issues affect a person’s life and well-being.

All of that, along with work on his PhD, helped Nigg develop a holistic view of ADHD that many in the field don’t have.

Stephen Hinshaw, a professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley, and a noted expert on ADHD, was Nigg’s mentor when Nigg worked toward his doctorate at UC Berkeley and has tracked his career closely. He said Nigg “clearly knows the underlying neurobiological vulnerabilities that shape ADHD. But he’s also been a pioneer in looking at environmental factors — including toxins in the environment — that have been overlooked for decades as potential additional causal agents” of ADHD.

And Hinshaw said: “He puts things together — rather than reducing it to biology versus environment.”

“It’s important to look at all the factors at play in this complex equation,” Nigg said about ADHD. “We want to get a better understanding of the biology, to go with our understanding of the social and behavioral side of this, and the psychological side of it. That integration is a really important theme in my work.”

If medicine can identify biological markers or social or behavioral predictors of certain types of ADHD, Nigg said, “that will help us know earlier who’s going to possibly get ADHD, and then that might be helpful to parents or clinicians.

“If you can turn the tables early on — before ADHD can emerge or before it can develop into these other problems — you can help a child get their life on track,”

Joel Nigg, PHD

“Maybe there would be different techniques parents could use to minimize the risk or effects of ADHD. There may be dietary changes that could help, or anti-inflammatory therapy. We’re researching to see whether some of those things could be true — and we’re fairly unique in that.”

“He’s relentless in his quest for knowledge,” said Hinshaw.

But Nigg said his research and pursuit of answers have been hampered — like they have for all ADHD researchers — by insufficient public attention to the problem. There’s little public understanding that improving outcomes for kids and adults with ADHD can be part of a solution to the pressing and related problems of depression, addiction and homelessness, he said.

“If we consider ADHD’s influence on these other conditions in terms of early development, it’s as big a factor as any of them,” he said. “And yet relative to its importance, ADHD gets overlooked and doesn’t get funded the way it should.”

Nigg said he is very appreciative of the philanthropic support his work has received from the Sharps even before their newest transformational commitment. That sort of private support is invaluable — and will be with the new center — because it allows him and the OHSU team to pursue pathways of research that likely wouldn’t get financial support from the federal government.

“We are grateful for all the federal grant support we have received. But to get federal grant support, you usually want really strong evidence of probable success,” Nigg said. “These are public funds and aren’t put into too many high-risk strategies.”

But high-risk strategies pursuing novel ideas can pay off with game-changing discoveries, Nigg said.

“With philanthropy, we can take bigger risks,” he said.

Nigg, a football fan, likens it to offensive strategies in the sport. “You can always try for a first down,” he said. “The National Institutes of Health naturally have a responsibility to be cautious and so they want to fund you to try to get a first down. That’s necessary and good. But to balance it, we want to go for the end zone sometimes, take a gamble on hitting big. And philanthropy enables us to do that.”

The successes from that work can then lead to more support from traditional sources.

“For every million dollars in philanthropy, our group has generated $5 million in federal grants,” Nigg said. “That’s because we can leverage our successes; the advances we make through philanthropy help us get more grants.”

All of that can lead to the ultimate goal, Nigg said: improving the future lives of millions of children and adults.

“If you can turn the tables early on — before ADHD can emerge or before it can develop into these other problems — you can help a child get their life on track. They can gain the freedom to make and carry out their choices and achieve their own calling. That, to me, would be the ultimate success.”

Your support can accelerate innovative, life-changing ADHD research.