By Josh Friesen

For Ignite Magazine

It’s hard to overstate the Kuni Foundation’s impact on cancer research and care at OHSU and the OHSU Knight Cancer Institute.

Since 2020, the Kuni Foundation has awarded 10 Discovery Grants and 24 Imagination Grants to cancer researchers at OHSU. The Kuni Foundation’s support totals $20 million, which has funded research for 39 principal investigators from 18 departments across the institution and established two endowed chairs for lung and prostate cancer. In 2024, Wesley Yu, M.D., director of the Melanoma and Skin Cancer Program at the Knight Cancer Institute, became the first Kuni Foundation Cancer Research Fellow. The Kuni Foundation is committed to advancing promising ideas that translate into catalytic methods of cancer detection, treatments and cures. Inspired by their founders’ profound commitment to innovation and community service, the Foundation’s investments in Discovery and Imagination grants, as well as endowed faculty positions, have helped researchers at the Knight Cancer Institute move ever closer to ending cancer as we know it.

“We believe that meaningful progress in cancer research requires courage, collaboration and the willingness to take risks,” said Angela Hult, Kuni Foundation president. “We support scientists who explore uncharted territories and challenge conventional thinking, and the more we invest in these bold approaches, the more it increases the chances for new breakthroughs and accessible, affordable treatments. Our support of OHSU’s transformative work reflects our deep commitment to advancing the kind of scientific innovation that saves lives and reshapes the fight against cancer.”

The OHSU Foundation caught up with four recent recipients of the Kuni Foundation’s generosity to learn how their innovative efforts are pushing us toward a future free from the burden of cancer.

Ramon Barajas Jr., M.D.

Kuni Foundation Discovery and Imagination Grant Recipient

Even with the best treatment, the median survival time for patients with glioblastoma — one of the most aggressive and deadly types of brain tumor — is 17 months.

Ramon Barajas Jr., M.D., an associate professor of diagnostic radiology in the OHSU School of Medicine and faculty member of the Knight Cancer Institute, is taking an unconventional approach toward extending that prognosis, potentially redefining treatment strategies not just for glioblastoma, but for brain tumors as a whole.

“It’s pretty exciting stuff,” Barajas said. “We’re at the knife’s edge of trying to advance therapies from a radically different approach.”

Much of glioblastoma’s aggressiveness stems from its ability to corrupt immune cells in the brain, tumor- associated macrophages (TAMs), to promote its own growth. Barajas’ research seeks to leverage the power of hibernation to reprogram TAMs in and around the tumor back to their original function, a process that would also activate other immune cells in the brain called microglia. By restoring TAMs’ original function and stimulating microglia, Barajas hopes to develop a novel immunotherapy to reconfigure the immune microenvironment, stop the tumor’s growth, and target and kill glioblastoma cells.

This approach leverages a pharmacological way to induce a hibernation-like state in a non-hibernating animal developed by Domenico Tupone, Ph.D., a research assistant professor in the Department of Neurological Surgery at OHSU.

“Induction of a hibernation-like state could be beneficial for the treatment of several pathologies,” Tupone said.

“We know that hibernation in animals basically causes the immune system to reset,” Barajas said. “When animals go into hibernation, a lot of their immune cells go back to the organ systems they arose from. So, you have this complex interaction with the immune system that we think we can leverage to reset the immune system, recirculate immune cells and then activate native immune cells.”

Though this research focuses on improving outcomes for glioblastoma, Barajas and his team are gaining knowledge that could lead to similar therapies for other diseases.

“We’ve been very focused on helping improve outcomes for glioblastoma,” Barajas said. “But the knowledge we’re gaining overall, if this pans out, could one day be widely applicable to many disease processes.”

“I think we have a great idea — I’m convinced we do. I’m convinced we have an idea that will help people, but it otherwise wouldn’t have seen the light of day if not for the opportunities presented to us by the Kuni Foundation.”

— Ramon Barajas Jr., M.D.

Claymore Kills First, Pharm.D.

Kuni Foundation Discovery Grant Recipient

Pancreatic cancer affects Native Americans more than any other ethnic group in the United States.

The disease is the 10th most diagnosed cancer in the country, yet it is the third leading cause of cancer- related deaths. Compared to the U.S. population, Native Americans in Oregon are twice as likely to be diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, and nationwide, Native Americans have the lowest survival outcomes of any other racial or ethnic group.

Claymore Kills First, Pharm.D., a clinical oncology pharmacist at OHSU, is trying to figure out why.

“There aren’t many studies that adequately include Native Americans to assess risk factors for cancer,” said Kills First, an enrolled member of the Oglala Sioux Tribe and Miniconjou Lakota. “We have known risk factors: diabetes, alcohol, obesity, smoking, and there’s familial, genetic components. But there’s never been any study that tried to confirm the correlation between these risk factors and pancreatic cancer in Indigenous populations. That’s what we’re trying to do.”

To shed light on the factors driving pancreatic cancer disparities among Native Americans, Kills First and his research team are leveraging existing relationships between OHSU and the Warm Springs reservation to study and address the barriers to clinical trial involvement within the tribal community. They then aim to replicate their study for additional tribal communities in Oregon. The long-term goals of these collaborative studies are to increase Native American enrollment in pancreatic cancer clinical trials and develop a first-of-its-kind Native American pancreatic tissue registry to determine if and how Native Americans have genetic predispositions to pancreatic cancer.

The first step toward those goals, however, is building trust and collaboration, a foundation of which OHSU is establishing through efforts such as the partnership between the Brenden-Colson Center for Pancreatic Care and the Knight Cancer Institute’s Community Outreach, Research, and Engagement (CORE) program.

“We have quite a few Native American faculty in the School of Medicine, we have the Northwest Native American Center of Excellence, and we have joint partnerships with our providers out in tribal clinics who are doing such good work,” Kills First said. “OHSU is doing a great job to bridge these gaps and to rebuild these trusts. Our research team has sought to utilize those relationships as points of contact and build our own.”

“We wouldn’t be where we are today and wouldn’t have made the progress we’ve made without the support of the Kuni Foundation. I think myself and our whole research team is very aware of that, and we’re very, very thankful.”

— Claymore Kills First, Pharm.D.

Amy Moran, Ph.D.

Kuni Foundation Discovery Grant Recipient

Amy Moran, Ph.D., never set out to establish the intersection of sex hormones and cancer treatment as a whole new field of cancer research.

But when her 2022 study in Nature demonstrated how testosterone receptor suppression improves immunotherapy outcomes, that’s exactly what she did. It has led to a world of opportunity that has the potential to add a breakthrough style of treatment to the cancer-fighting arsenal.

“This is never what I thought these studies would reveal. But it has,” said Moran, an associate professor of cell, developmental and cancer biology in the OHSU School of Medicine and a faculty member of the Knight Cancer Institute. “It’s opened a door that has led to a tremendous number of people around the world looking at sex hormone differences in cancer — cancer adverse events, cancer outcomes, drivers of cancer and cancer treatment outcomes — and that is exciting because it adds a critical layer of the whole person, their hormones, to the personalized medicine approach.”

The seeds of Moran’s research date all the way back to the 1940s when cancer researcher Charles Huggins discovered that prostate cancer uses testosterone as fuel to grow, a breakthrough that led to testosterone deprivation therapy as a treatment and a Nobel Prize.

In the years that followed, researchers haven’t really explored how testosterone affects other types of cancer beyond breast cancer. Moran’s research, however, is the first in the world to focus solely on how testosterone decreases the effectiveness of immunotherapy drugs.

At first, Moran’s research focused on T cells — a type of white blood cell the body produces to help fight cancer. She has extended this work to reveal that cancer uses testosterone to hide from the immune system. The next step of Moran’s research aims to begin building a more holistic picture, broadening the investigation to other immune cells to determine the impact of hormone suppression on the entire immune cell landscape in other diseases such as melanoma and breast, liver and bladder cancer.

If Moran’s upcoming research yields results similar to those her team found in testosterone and T cells, it could revolutionize cancer treatment as we know it.

“This has shed unbelievable light on how many different tumor types might be using testosterone to support the tumor and suppress the immune system,” Moran said. “It’s provided a novel, targetable pathway in patients harnessing readily available testosterone blockers in cancers where this is not standard of care. We have clinical evidence that those patients might benefit

from this treatment, improving the activity of their immunotherapy.”

“The Kuni Foundation’s investment in my work and in my lab has had such a large impact on human health and has given people more birthdays, more anniversaries. This is critical. It’s a catalyst for innovation.” — Amy Moran, Ph.D.

Naoki Oshimori, Ph.D.

Kuni Foundation Imagination Grant Recipient

Cancer drugs have come a long way toward extending not only the length of life, but the quality of life.

For many whose cancer has gone into remission, however, the fear of it returning lingers. For as long as there has been research working to eliminate cancer, there has been research working to keep it from coming back.

Naoki Oshimori, Ph.D., an associate professor of cell, developmental and cancer biology in the OHSU School of Medicine and a faculty member of the Knight Cancer Institute, has shed light on the molecular mechanisms behind cancer recurrence and is using this newfound understanding to deprive cancer of its ability to return.

“How to prevent recurrence is one of the key questions in cancer research, at least in my mind,” Oshimori said.

The human body owes a lot of its longevity to how its stem cells regenerate and repair tissue — an ability enhanced by a stem cell’s capacity to remain dormant deep within niche microenvironments where their activation is regulated, and their stability and sustainability are protected.

Oshimori recently published a study that discovered how tumors develop their own dormant cancer stem cells, or CSCs, in their niches in tandem with their own growth. Like our bodies’ stem cells, CSCs manage to shield themselves from harm, which, in their case, takes the form of chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Even if cancer treatment eradicates the majority of CSCs present in a tumor, the remainder can lead to that cancer’s revival due to their niches.

Oshimori’s current research hopes to target the molecular signal secreted by CSCs to undermine its niche microenvironment within the tumor, thus removing its stem-cell-like properties and deactivating its ability to regenerate the tumor.

“Our target is the environment,” Oshimori said. “If we could disrupt the critical environment and destabilize the stem-cell property of these dormant cancer cells — because that is the key to cancer cells regenerating the tumor — the tumor can’t come back. That is the

ultimate goal.”

“The Kuni Foundation, they hear our voice. They trust us. That support is very encouraging to have from such a prestigious foundation.” — Naoki Oshimori, Ph.D.

The value of private philanthropy

Today’s scientific research informs tomorrow’s possibilities, and private philanthropy is imperative — perhaps now more than ever. The Kuni Foundation’s backing is vital to researchers like Barajas, Kills First, Moran and Oshimori and supports the graduate students and post-docs working in their labs. More so, it encourages the scientists to let their curiosity guide their research, ask bold questions and helps fund pilot studies that yield answers full of promise.

Full of opportunities.

Full of hope.

Those answers may go on to elicit more research funding from larger entities like the National Institutes of Health or the American Cancer Society. But that initial support from places like the Kuni Foundation is the spark of innovation that ignites the flames of change.

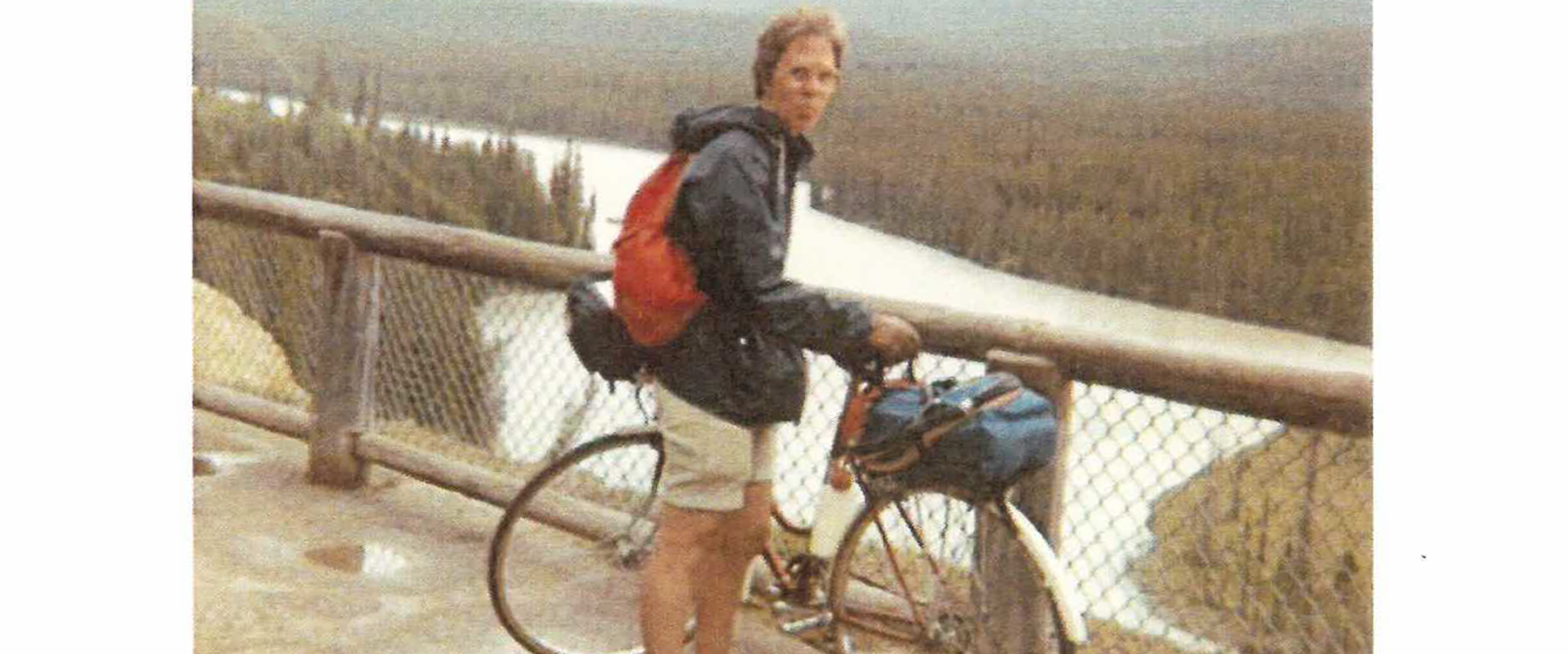

Pictured at top: Kuni Foundation support is enabling OHSU teams to engage with the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs and other tribal communities to understand and address their unique barriers to cancer screening, treatment and clinical trials. (OHSU)