John S. Wold was a businessman, geologist, inventor, a former U.S. congressman and a philanthropist. In the last 20 years of his life, macular degeneration — a blinding eye disease — came between him and the things he loved the most. He was passionate about supporting research to stop the disease and return vision to those who suffer from it.

In June 2018, after John passed away, the Wold Foundation of Wyoming donated $2.5 million to Casey Eye Institute. That gift, in addition to John Wold’s gift of $5 million in 2015, will build and support the Wold Family Macular Degeneration Center. Priscilla Longfield, Wold’s daughter, delivered the following heartfelt tribute at a meeting earlier this year to honor her father and tell why finding new treatments for macular degeneration meant so much to him:

“I want to tell you about a man who was one of my heroes, a man named John Wold who died a year ago February at the age of 100. He was my father.

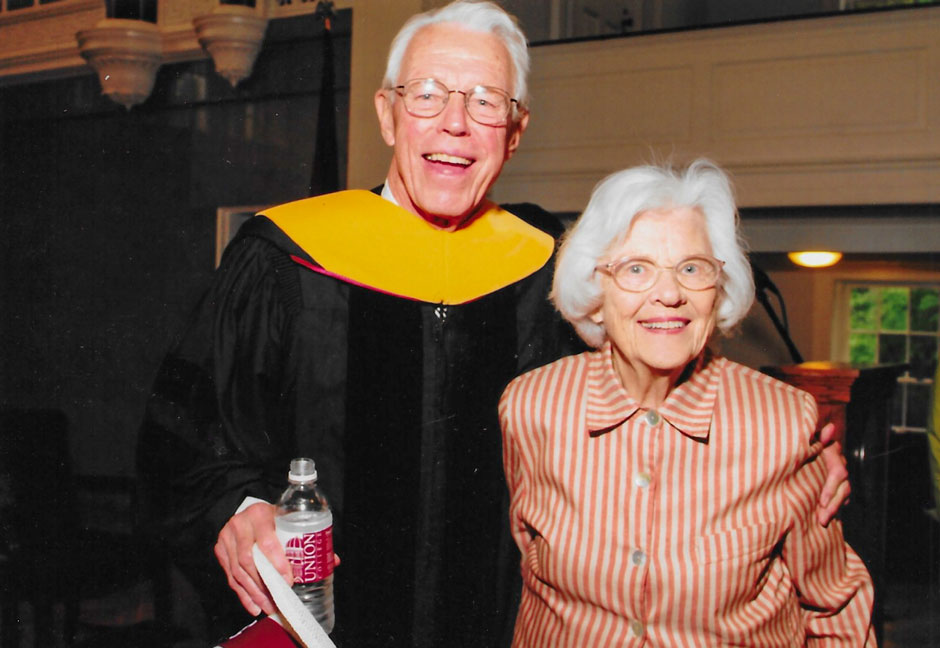

My parents, both originally from upstate New York, moved to Casper, Wyo. in 1949 and lived there for 68 years. My father was the son of a nationally recognized physicist, and dad spent a lot of time as a kid in scientific research labs on the campus of Union College. For many summers he was a lab assistant to the famous scientist Irving Langmuir, who was the 1932 Nobel Prize Winner in Chemistry and a close protégé of Albert Einstein’s. During dad’s high school summers he traveled throughout upstate New York with Langmuir conducting chemistry and hydrologic experiments on lakes in the Adirondacks.

That scientific curiosity was in dad’s DNA and was a driving force in his activities for the rest of his life. He was the recipient of a number of patents from the U.S. Government Patent Office. His first was for the design of underwater goggles, another for in-situ mining of the mineral trona, and at age 92 he received a provisional patent for the design of eyeglasses to aid those whose sight is ravaged by macular degeneration. Shortly after, scientists from Bausch and Lomb and several universities approached him for discussions of his hypothesis.

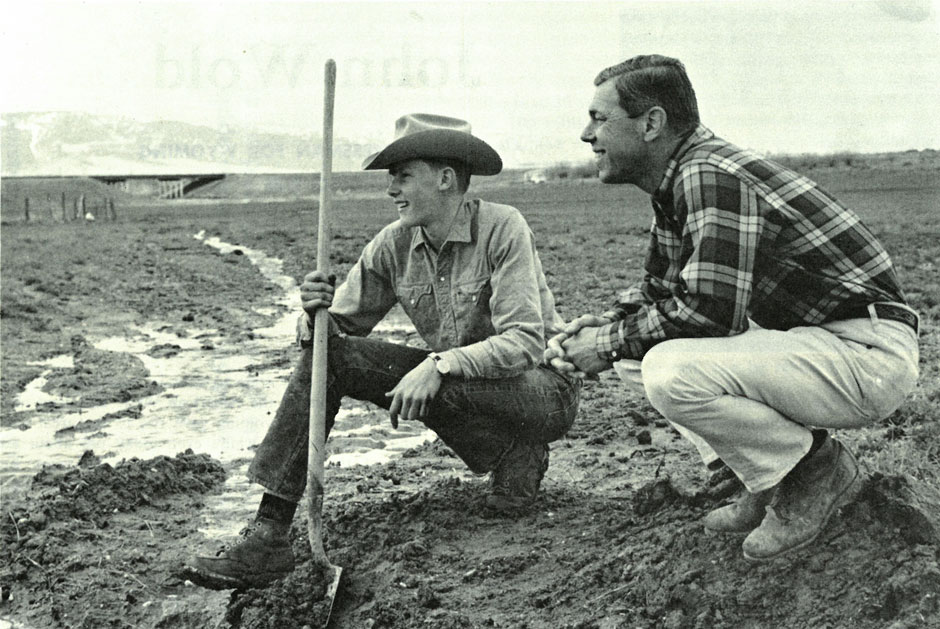

My father wore many hats during his life: passionate family man, rock hound, geologist, scholar, scientist, inventor, Eagle Scout, naval officer, legislator, U.S. Congressman, businessman, rancher, athlete, sport’s coach, mentor, entrepreneur, philanthropist, educator, friend and dreamer. He spent a lot of time dreaming about the future.

His big dreams lead to big accomplishments. His passion was work, and that’s how the Cub Scout became an Eagle Scout, the high school cum laude student became a St. Andrew’s and Cornell University scholar, how the young canoe paddler became a lieutenant commander in the U.S. Navy serving in the Atlantic and Pacific theatres during World War II, how a young rock hound became a geologist and the recipient of so many industry and civic awards and recognitions; how a young ski fanatic and hockey player became the force behind the construction of a local ski area and ice arena; how a once defeated school board candidate went on to become a U.S. Congressman; how a sufferer of macular degeneration got involved with the Casey Eye Institute and became passionate about finding a cure for that devastating disease.

About 20 years ago, the telltale signs of vision loss became frighteningly apparent to dad. His first symptoms were typical — blurriness, and a distortion of his central vision. He was losing the clear definition of letters on a page. After being tested in Denver and in New York, he was diagnosed with early stage macular degeneration, the dry form for which there is still no treatment. In retrospect, it was not surprising. Both his mother and older sister had suffered from the disease. Family history plays a big role in macular degeneration. My mother, at the time said, “This is the first chink in your father’s armor.” Knowing about dad’s drive to accomplish, you can understand that the diagnosis of macular degeneration presented him with a huge challenge.

How did the disease affect his life?

First, he lost the ability to read standard print. Dad was a voracious reader, not of fiction but of work related material, scientific journals and articles. In the beginning he compensated, first with a magnifying glass and then by enlarging the size of the print of everything he wanted to read. Eventually with the help of Dr. John Boyer at Casey Eye Institute’s Low Vision and Rehabilitation Clinic, dad obtained a machine that would scan one page at a time and read it to him. But the machine was complicated and hard for him to see the correct buttons to push so he needed someone with him all the time.

Dad was a consummate fly fisherman. He loved fishing the waters of the Powder River in Central Wyoming probably more than any other activity. But after losing the ability to tie the fly on the line, and see his cast, he lost interest going to the places he loved most in the world.

Two years ago my father very much wanted to read a poem at the funeral for my mother, his partner and wife of 69 years. Despite the enhanced print size, he was still unable to make out the words on the page and therefore unable to participate in her service. That made him angry and frustrated.

As he aged, dad’s balance got shaky and he had a constant fear of falling. Out walking, he couldn’t see a curb, a heaved sidewalk or holes in the street. These things tripped him up and it was humiliating for him.

“Two years ago my father very much wanted to read a poem at the funeral for my mother, his partner and wife of 69 years. Despite the enhanced print size, he was still unable to make out the words on the page and therefore unable to participate in her service. That made him angry and frustrated.”

There were some humorous moments …

My older brother, Peter, recalls getting a ride home from the office with dad one day. Dad casually remarked to Peter, “You know I really can’t tell the difference between a red light and a green one.” It was at that moment that we began the uphill battle to stop him from driving. Due to his inability to read the questions on the online driver’s test, he was forced to relinquish the steering wheel — at the age of 95.

By the time dad’s eyesight began to really deteriorate he’d started shifting his primary focus away from his business deals and activities. He’d already achieved international recognition for his work in the mineral industry. He felt the need to concentrate more on philanthropic opportunities, to give back.

He was becoming more and more frustrated that so little progress had been made on the early diagnosis, prevention and treatment of macular degeneration, a disease that had been recognized for over a century. He was determined to help in the effort to find a cure.

For him, it was a matter of extreme urgency, and he was eternally hopeful — perhaps naively so — that a cure would be found to restore his vision in his lifetime.

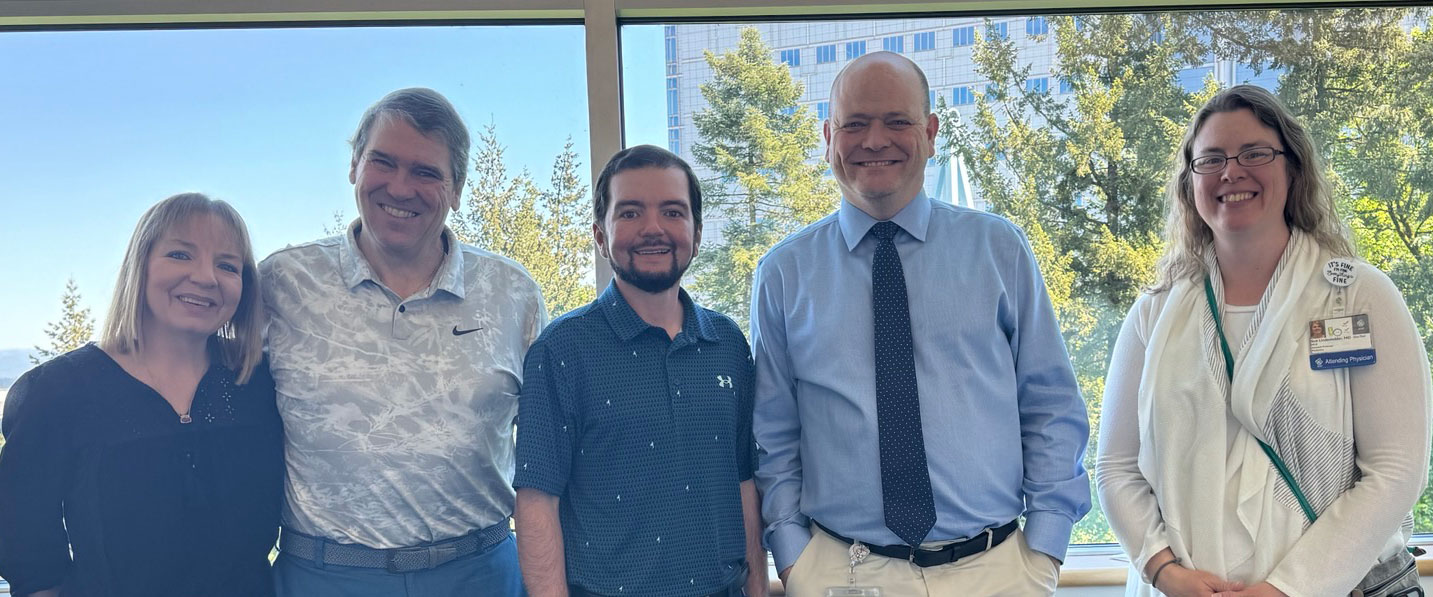

Macular degeneration robbed my father of his eyesight, but he never lost his vision, and in 2015 he was introduced to Dr. Dave Wilson and his team at OHSU Casey Eye Institute. He was so impressed by them that he made a gift to Casey to support a macular degeneration research lab for Casey’s new facility, scheduled for groundbreaking in 2018.

“For him, it was a matter of extreme urgency, and he was eternally hopeful — perhaps naively so — that a cure would be found to restore his vision in his lifetime.”

Macular degeneration may not be a household name to many people today but that will change. As the population continues to live longer, the incident rate will rise. Today, macular is the nation’s leading cause of legal blindness.

There are no easy fixes. This is a very complex disease, caused by many factors. Casey over the last couple of years has made major breakthroughs in the area of genetics, optical imaging, and gene therapy. They have amassed a large database, demonstrating the significant role that family history plays. The advances they’ve made in optical imaging is proving key to new treatment and to early detection. It was announced in December that Casey will be one of four centers nationwide to provide new gene therapy treatment. Casey now has more ongoing macular degeneration clinical trials than anywhere in the world and patients come to Casey from all over the world.

I am so sorry that my father didn’t get involved with Casey earlier in his life and see firsthand the progress that is being made to cure this most debilitating and increasingly common disease. He would have found the science and Casey’s progress thrilling!

There is no cure yet for macular degeneration but researchers at the Casey Eye Institute are poised to change that.

Thank you for the honor you’ve given me to talk about my father and the battle he so bravely waged and so many wage today with this dreadful disease.”