Alzheimer’s disease is cruel and unrelenting. By the time a person or their loved one begins to notice cognitive decline – trouble paying bills, remembering to take medication or go to a doctor appointment – the disease has been lurking in the brain for years.

In 20 years of drug trials, there has been no good news, and the emotional and financial toll of dementia on families and caregivers is overwhelming.

If there is no treatment for Alzheimer’s yet, how can we detect it earlier? How can we prevent it? And are we looking at the right targets for medications? Finding answers to these questions requires state-of the-art imaging equipment, a deep understanding of the causes of dementia, a talent for collaboration – and tenacity. That’s why Lisa Silbert, MD, is such a good fit for the challenge.

“What makes Dr. Silbert so special for OHSU – and really a national treasure to our research community – is her unique intelligence,” says Jeffrey Kaye, MD, director of the Layton Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease Center. “She’s able to see the big picture in the field while also being so effective at focusing on the critical details, from pixels to personal needs of staff and other investigators.”

Silbert is the inaugural Gibbs Family Professor in Neurology at OHSU and director of the Neuroimaging Core at the Layton Center. While she oversees an entire team of researchers at the center, her specific research focus is on the white matter lesions in the brain that cause dementia. Her numerous publications on Alzheimer’s and dementia research have been cited more than 2,000 times.

Help OHSU create hope for people living with Alzheimer’s disease.

Silbert is one to watch, says Charles DeCarli, MD, Director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Center and Imaging of Dementia and Aging (IDeA) Laboratory of the University of California at Davis. DeCarli has collaborated with Silbert and says he often cites her work. “She has developed an excellent neuroimaging program at OHSU.” he says. “She is a ‘rising star’ in vascular cognitive impairment research, and I expect more great things to come from her scientific endeavors.”

A national resource

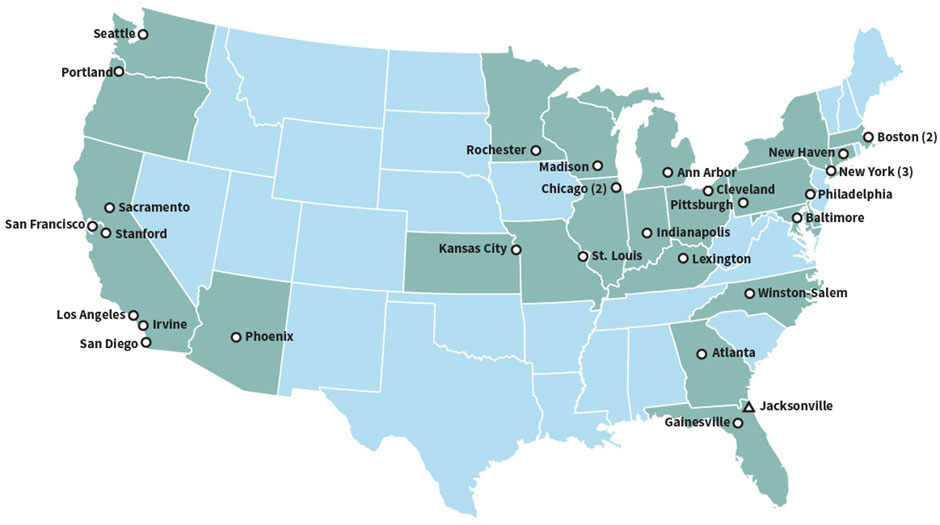

The Layton Center is one of a network of 31 Alzheimer’s disease research centers across the country funded by the National Institute on Aging, part of the National Institutes of Health. Layton Center investigators are producing some of the most novel findings in the field today. Being part of that network is meaningful — particularly to donors and research subjects — because all the data collected at OHSU is shared with the other ADCs and leveraged for greater impact.

The OHSU Layton Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease Center is one of 31 NIH-funded Alzheimer’s disease centers across the nation. Source: NIA.nih.gov

In 2017, the NIH designated OHSU’s Neuroimaging Core as an official core for having special expertise in neuroimaging and aging research. Neuroimaging is key to understanding dementia, so the core is a significant part of what makes the Layton Center and its scientists so highly regarded across the country.

Breaking down a complex subject

Silbert is often asked to break down the science behind dementia for donors and other audiences. That’s in her free time, when she’s not doing research, publishing papers, seeing patients, teaching graduate students or monitoring brains as patients undergo neurosurgery.

She explains that scientists prefer to use the term Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders because that covers the broader umbrella of dementia. Alzheimer’s disease, the most common cause of dementia, involves amyloid plaques that build up in the brain more than 10 years before the onset of cognitive symptoms. Later, tangles of a protein called tau block neurons from communicating.

The second most common form is vascular dementia, which is like heart disease of the brain. Less common are other types: Lewy Body dementia, frontotemporal dementia and other age-related brain changes. Silbert notes that people with dementia usually have a combination of multiple types of these dementias – not just one.

“It may not be what pathology you have necessarily, but how many you have and how well your brain can actually combat different pathologies,” Silbert explains. “If your brain is super healthy, you may die with some Alzheimer’s pathology and never know it, whereas someone who has had a couple of strokes or major head trauma might manifest clinical symptoms with that same amount of Alzheimer’s pathology.”

Expertise in imaging

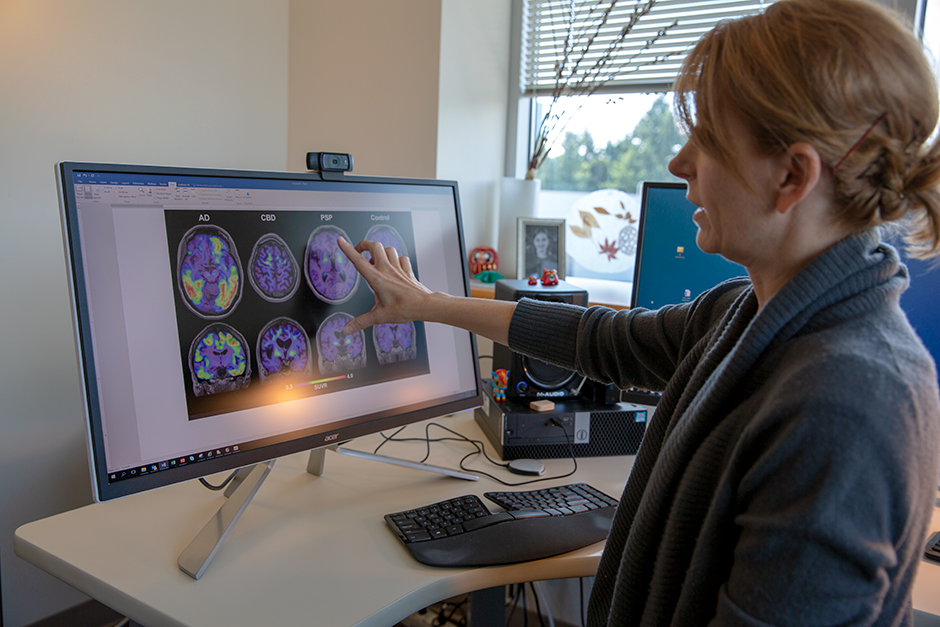

The Neuroimaging Core that Silbert directs uses two key types of imaging to study the brain. The first, MRI, allows researchers to study brain structure and volume, such as atrophy of the hippocampus and the temporal lobe – areas that are impacted by Alzheimer’s disease.

For vascular dementia, researchers are looking for white matter lesions in MRI. In the case of Silbert’s own research, OHSU’s 3T MRI helps her investigate cerebral blood flow

“This is extremely exciting. Having amyloid and tau PET tools gives me the most hope that we will find more effective treatments for Alzheimer’s and possibly even prevent the disease before it starts.”

Lisa Silbert, MD

The other, newer type of imaging is amyloid and tau Positron Emission Tomography (PET). When Silbert began her career, she says, the only way to confirm an Alzheimer’s diagnosis was after death, when the pathologist could look at brain tissue under a microscope. Now, thanks to advances in the last 10 years, scientists can identify the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease (amyloid and tau) in the brains of living subjects using PET scans. With PET, OHSU’s scientists can see these deposits, not just the brain structure and atrophy. If you can see the pathology, you can see how medications work to stop it.

PET scans have been available at OHSU for several years, but amyloid and tau PET are new to the field. In 2016, when OHSU launched the Center for Radiochemistry Research with support from Phil and Penny Knight, the university installed a cyclotron – a particle accelerator that’s used to produce radioactive isotopes called ligands. Before OHSU had its own cyclotron, researchers had to have ligands flown in from across the country, and then had to use them quickly because of their short half-life. Silbert is thrilled to be able to develop novel PET ligands for dementia research at OHSU.

“This advancement is extremely exciting,” she says. “We can now look at risk factors and treatment effects in relation to the actual underlying pathology, rather than just clinical symptoms, which are not always specific to Alzheimer’s disease. Having amyloid and tau PET tools gives me the most hope that we will find more effective treatments for Alzheimer’s and possibly even prevent the disease before it starts.”

Amyloid and tau PET scans are not ready for clinical use, Silbert says. They are not FDA approved, they are not covered by insurance, and they are very expensive. However, they are a significant part of research, and almost all clinical trials require them, particularly if a trial is targeting amyloid or tau – those key markers of Alzheimer’s. PET imaging is a high-opportunity area where philanthropy can further Alzheimer’s research, and Silbert would like to be able to offer MRI, amyloid, and tau imaging to all Layton Center patients someday.

Unprecedented research fueled by philanthropy

Thanks to seed money from the John L. Luvaas Family Fund of the Oregon Community Foundation and a gift from an anonymous donor, PET imaging will be one of a multitude of data points collected on subjects as part of the BRIGHT study, the most comprehensive of its kind to date.

The BRIGHT study will collect novel biomarker data from 50-75 participants who may be at high risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease using technology in the home (digital biomarkers such as computer use), the blood (looking for neuronal loss, inflammation, vascular risk, lipid metabolism, genetics, etc) MRI (blood flow, vascular disease, hippocampal and brain volumes, etc.) and amyloid PET imaging – all cataloged to create a detailed view of who may be most likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease.

Through the BRIGHT study, investigators will gather the preliminary data needed to apply to the NIH’s National Institute on Aging to launch future clinical trials for therapies that might prevent dementia. The goal is to know when a prevention therapy works without having to wait until a person develops advanced Alzheimer’s disease.

Philanthropy is key to helping get promising ideas like the BRIGHT study off the ground. Indeed, donor support has been the catalyst for many significant initiatives throughout the neurosciences at OHSU, including an investment in unsurpassed imaging capability that is the hallmark of the university. That capability, in turn, helps drive discovery and train the next generation of scientists and physicians through OHSU’s highly esteemed neuroscience graduate program.

Philanthropy also helps attract and retain the very best minds in science when it’s used to endow a position like Silbert’s. She says having the Gibbs Family Professorship in Neurology helps her dedicate more time to research and add additional staff to support her work.

“I am extremely honored to have received this professorship,” Silbert says. “It was a validation of a lot of hard work, but more than that, it was encouragement to continue on with this exciting work to end Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.”

Dr. Silbert has received funding for her research from the Alzheimer’s Association, the American Academy of Neurology Foundation, and the NIH/NIA, including a K23/Paul B. Beeson career development award in aging research and R01s. She has also received support from the Storms Family Fund, the Max Millis Fund, the T&J Meyer Family Foundation and Dan and Lois Gibbs.

Help us find promising treatments for Alzheimer’s disease.