One evening in 2017, Mary* brought her child to the emergency department at OHSU Doernbecher Children’s Hospital. After hours of tests and meetings with doctors, her child was admitted.

It was late, the cafeteria was closed at that hour and Mary had skipped dinner while they were in the ER. Morning came, but she didn’t want to leave her child’s bedside because she was scared she’d miss the doctors on rounds. More than 16 hours passed before she finally ate.

Mary’s story is one of hundreds that inspired the creation of the Nourish program at OHSU Doernbecher.

Evidence and Experience

Nourish is the brainchild and passion project of Louise Vaz, M.D., M.P.H.; Laurel Hoffmann, M.D., M.P.H.; Kim Dody, RN; Rebecca Jungbauer, Dr.P.H., M.A., and Anne Bateman, RN (ret). Its mission is three-fold: Prevent hunger for caregivers during hospitalization; destigmatize the experience of needing food resources; and identify families experiencing food insecurity at home to connect them to community food resources that can ease their transition to outpatient care. The Nourish team runs the program as volunteers outside of their respective roles at OHSU.

Nourish emerged from the Most Vulnerable Project (MVP), a research study Vaz and several Doernbecher collaborators started in 2017 with funding from the Friends of Doernbecher and the Collins Medical Trust. Vaz is an infectious disease specialist at Doernbecher, as well as an associate professor of pediatrics (infectious diseases) in the OHSU School of Medicine. Her research has focused on exploring social determinants of health that impact outpatient care.

“Every family at Doernbecher is food insecure…because no parent wants to leave their child’s bedside for even a minute.”

Rebecca Jungbauer, Dr.P.H., M.A.

MVP surveyed 265 patient families about their experiences at Doernbecher and the non-medical challenges they faced while their children received inpatient care. What the MVP found was daunting: 1 in 3 families at Doernbecher are unable to afford basic needs — such as food, housing or utilities — at the time of their child’s hospitalization.

“It was humbling when you see it on a piece of paper,” Vaz said. “I think we all have our individual stories, but we don’t take the big context into it.”

Vaz and the MVP team turned to Bateman for insight on how to help. At that time, Bateman worked with the Quality Safety Team, which is responsible for involving patients’ caregivers, or “parent-partners,” in the policies and programs at Doernbecher. Together, they conducted focus groups with parents and asked them to rank their unmet needs.

Parents overwhelmingly identified hunger as their greatest challenge.

Food Insecurity and Patient Care

Food insecurity is a pervasive social issue both nationally and within Oregon. A child’s hospitalization often exacerbates food insecurity for families and can create insecurity among those who haven’t experienced it before.

“Every family at Doernbecher is food insecure,” Jungbauer said. “Whether they’re poor or wealthy, because no parent wants to leave their child’s bedside even for a minute. They would rather go without food themselves than leave their child.”

Having a child in the hospital is an inherently stressful experience. Parents are often scared: that they’ll miss a doctor on rounds, that they’ll get bad news or that they aren’t equipped to handle their child’s changing needs. The Nourish team noticed that caregivers sidelined their self-care in order to be present for their children.

During the MVP focus group, one mother confessed, “I would take what [my son] didn’t eat — it was pretty much glossed over — that is how I ate for two weeks.”

Support the Nourish Program at OHSU Doernbecher Children’s Hospital

Many patients are too young to notice or understand when their caregivers forego food, but every patient is impacted when their caregiver goes hungry. When caregivers don’t eat, it impairs their ability to be fully present for their children during a critical time. Hunger affects the ability to understand information, plan ahead and advocate for patients with staff.

Vaz and her team decided they needed to do something about hunger among caregivers. They knew that by tackling this issue while families are at Doernbecher, they could lay the foundation for higher quality care in outpatient settings.

“Moving forward and making a difference with one thing can have cascading effects that might impact a family in a positive way.”

Louise Vaz, M.D., M.P.H.

“We felt motivated to move on something that we knew was a problem. We were trying not to feel paralyzed by the gravity of the problem or how big and interrelated it is,” Vaz said. “Moving forward and making a difference with one thing can have cascading effects that might impact a family in a positive way. So even though it seemed daunting, we wanted to try something, however small it was. And that’s where we are with Nourish.”

So, they took action.

Filling the Eligibility Gap

Today, if you visit inpatient units 9 North, 9 South or 10 North, the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) or the emergency department at Doernbecher, you might see an unassuming cabinet with a plaque that reads “Annie’s Pantry.” The pantries are unlocked and stocked with non-perishable foods.

They’re the lasting legacy of Bateman, their namesake, whose determination to get families fed before her retirement in 2020 created the first eligibility-free caregiver hunger program at OHSU. Any family can access the array of foods in the pantry. The only requirement: having a family member who is currently receiving care at Doernbecher.

The Nourish program manages these pantries as part of its mission to combat food insecurity.

Doernbecher currently has food programs available for some of the families in need. “Fulton Trays” are available for caregivers who live more than 50 miles away or who are currently breastfeeding the patient. Yet Dody notes that the majority of people using Annie’s Pantries are ineligible for any program, such as families who live in Portland but are unable to afford transportation home and mothers who are breastfeeding a patient’s younger sibling. This eligibility gap is where the Nourish program sees the greatest room for change.

“We saw the ways people were falling through the cracks and going hungry,” Dody said. “We just want to make sure that everybody is taken care of.”

The Nourish team received seed funding for the pantries from a private donor with a surprising connection. For many years, Bateman assisted with the palliative care of an adult patient. That patient’s daughter, in a gesture of gratitude and support, made a one-time gift of $5,000 to help get the pantries created and filled. This generous donation ensured that Bateman could achieve her goal of establishing the pantries before her retirement.

However, Dody, who now fills Bateman’s role on the Quality Safety Team, says the Nourish team has more fundraising to do. The pantries have been so successful that current demand required the program to spend the entirety of the seed funding within four months.

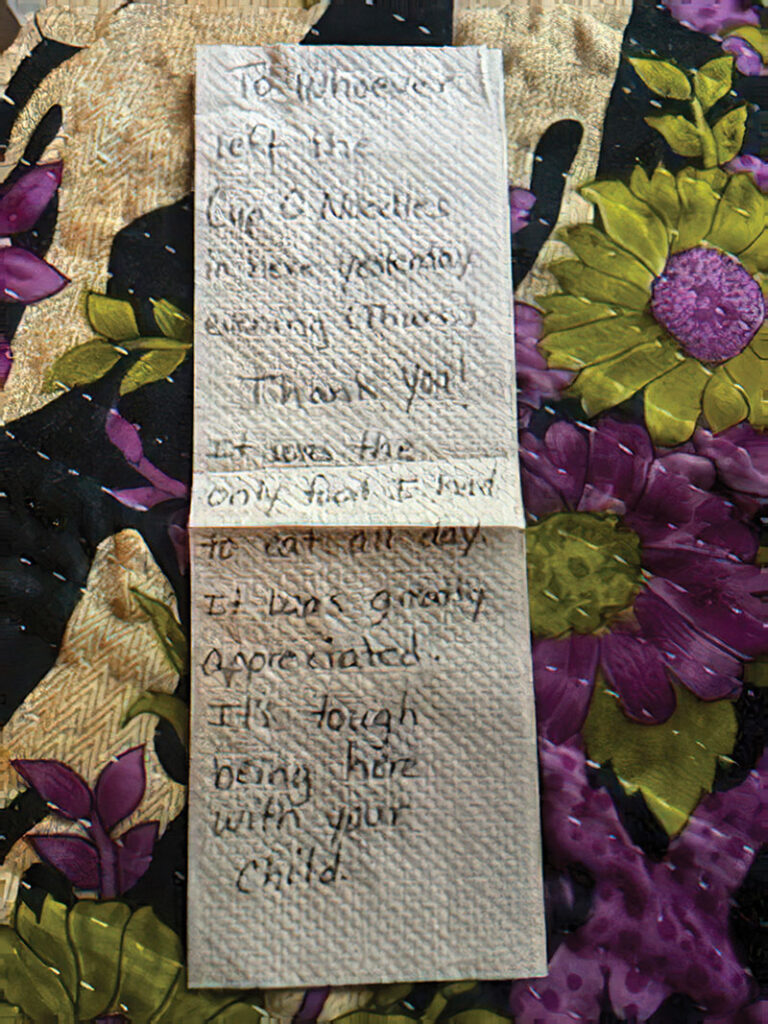

A handwritten note left for Kim Dody, RN, by a grateful parent. It reads, “To whoever left the Cup-O-Noodles in here yesterday evening (Thurs.): Thank You! It was the only food I had to eat all day. It was greatly appreciated. It’s tough being here with your child.”

Rite Aid Healthy Futures Exceeds Expectations

In October 2021, the Nourish team applied for $95,000 from the Rite Aid Healthy Futures Connecting Communities grant program. They hoped to use those funds to increase the accessibility of the pantries, create universal food insecurity screenings for patient families and include fresh foods in their offerings.

Rite Aid Healthy Futures counteroffered with $140,000 — a rare decision in grant-making.

“We couldn’t believe it,” said Vaz. “I think someone there recognized our efforts and saw, maybe, a similar vision.”

This grant has empowered the Nourish team to start building a sustainable future for the program. They opened the newest Annie’s Pantry in the emergency department and established the “Dolly Trolley” mobile pantry that reaches parents in isolation. They are also ordering refrigerators, which will enable them to include more fresh foods in their offerings.

Most critically, they will hire a program coordinator. This person will be responsible for creating partnerships with community organizations like the Oregon Food Bank and Veggie Rx; collaborating with Medicaid brokerages on meal reimbursements; and ultimately building a program that will continue to support caregivers long after the Nourish team joins Bateman in retirement.

They also see the Nourish program as an opportunity for Doernbecher on the national stage.

“This could really launch the importance of [this work] out to other hospitals and have a ripple effect with Doernbecher as the national leader and model,” Jungbauer said. “That’s a lot of future benefits from just a single grant.”

Nourish and the Future

Vaz, Hoffmann, Jungbauer and Dody dream big, but they are also realists. They understand that, given fiscal challenges, they must continue to seek other ways to sustain their program, including philanthropic support. They regularly apply for grants and have submitted another grant application to Rite Aid Healthy Futures.

“If somebody wants to give us unlimited money, we will do the most amazing things,” Jungbauer said with a laugh. “But for now, we’re doing what we can with what we have.”

What they can do today is visible in the wards of Doernbecher through the grateful smiles and anonymous notes from parents who no longer need to choose between going hungry and leaving their sick child’s bedside.