Professor Show-Ling Shyng isn’t one to revel in the spotlight. Look her up on LinkedIn, and you’ll find her profile doesn’t exist. Google her name, and you won’t find many personal details either. What you will find, however, is a treasure trove of articles about her pioneering research on the regulation of insulin.

We sat down with Shyng to learn more about the woman behind the work. What we discovered was a warm, funny, eloquent scientist who is committed to combating diseases like diabetes. This is her story.

Humble beginnings

Growing up in Taiwan, Shyng’s family didn’t have much. Her father was a military man who had fled China during the war. Her mother had no formal education. “She was basically illiterate, but she had such an entrepreneurial spirit,” said Shyng. “She was constantly finding new ways to help make ends meet.”

Shyng and her siblings were often recruited to help out with her mother’s ventures, which included making beaded purses, doing crochet work, and running a noodle stand. “We were always a part of my mom’s workforce,” she laughed. “But no matter how rough life was, we were still having fun.”

While some teens rebel against the idea of homework, Shyng had to rebel for it.

Shyng quickly realized that academics would be her way of rising above her circumstances. She managed to get into the best all-girls’ high school in Taipei, and began a grueling schedule that started at 5 a.m. each day. Getting to school required biking to the train station, riding an hour into the city, grabbing a bus, then repeating the whole thing in reverse each evening.

While some teens rebel against the idea of homework, Shyng had to rebel for it.

Upon arriving home, she was still expected to help her mother with the housework, which included assembling zippers to make extra money. “Tubs and tubs of zippers,” she said. “My hands would get raw from zipping them together.”

While some teens rebel against the idea of homework, Shyng had to rebel for it. “I pushed back a few times, because otherwise I wouldn’t have time to do my studies. If I was going to do well, that had to come first,” she explained.

Finding her path

Although Shyng had always been interested in science and medicine, she originally started training to become a teacher. That didn’t prove to be a good fit. “Delivering the same material over and over again didn’t seem very interesting to me,” she said. “In high school, I was really into biology, so I decided to transfer to National Taiwan University and get a degree in zoology.”

After graduation, Shyng decided to continue her studies abroad and landed at the neurobiology program at Cornell. She admits that her newfound independence was a bit unsettling at first.

“Living with my parents in Taiwan, I didn’t have much of a social life. When I would go out with friends in the States, I’d look at my watch and think, ‘It’s 9:00 pm! I’ve got to get home!’” she laughed.

Upon finishing her PhD at Cornell, Shyng headed to Cal Tech to begin her post-doctorate work, studying the mechanisms that control learning and memory. The move to California was an important milestone, but not for scientific reasons — it’s where she met Bruce, the man who would become her husband a year later.

After leaving her first post-doc, the newlyweds headed to St. Louis, where Bruce was doing post-doc work at Washington University. In the meantime, Shyng had to wait for her work visa to come through, a process that took six months. “I was making a lot of sandwiches for my husband,” she smiled. “It was a pretty humbling experience.”

With her work visa finally in hand, Shyng did a second post-doc at Washington University, studying the proteins associated with mad cow disease. It wasn’t the field she had trained in, but it exposed her to the science of how misbehaving proteins cause disease, an area that would prove to be instrumental in her current research. In the midst of all this, the couple welcomed two daughters, Jaeda and Kyra, to the family.

Welcome to OHSU

After the couple finished their post-doctorates, they began their job search in earnest. The catch was finding a place that had positions for two scientists. As it turned out, that place was the Center for Research on Occupational and Environmental Toxicology at OHSU.

So in 1999, the couple packed up their girls (their son Kian would be born at OHSU) and headed to Portland. Shyng eventually moved to the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, where she began her life’s calling — exploring how gene mutations disrupt the release of insulin.

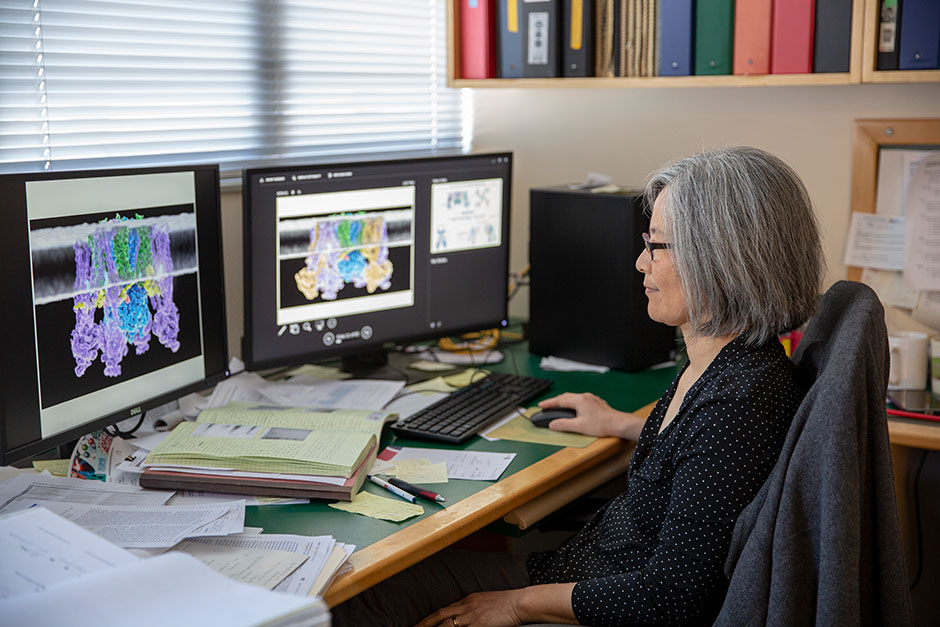

In the lab that bears her name, Shyng studies the molecular machinery in our bodies that sense changes in blood sugar. This particular molecular machinery is called a KATP channel, which controls insulin release. If these channels aren’t functioning properly, insulin is no longer regulated and blood sugar gets out of whack. Too low, and you become dizzy and pass out. Too high, and you could become diabetic.

A Christmas gift

Shyng’s goal is to help create drugs that can help regulate how much insulin is released by the pancreas. But to do that, first she needed to get a detailed view of the broken channels she was trying to fix. “I wanted to see how this machine works at the atomic level to understand how it moves and interacts with other molecules in the body,” she explained.

“Getting a high-resolution structure of these channels has long been the holy grail in my field,” said Shyng.

She wasn’t alone in her quest. For decades, scientists all over the world had been grappling with the same problem — but imaging technology wasn’t advanced enough to show them what they wanted to see. “Getting a high-resolution structure of these channels has long been the holy grail in my field,” she said.

“Getting a high-resolution structure of these channels has long been the holy grail in my field.”

Show-Ling Shyng, professor at OHSU

Then, on Christmas day of 2015, Shyng got her wish. She was in the lab, working with her student Greg Martin and colleagues James Chen and Craig Yoshika. Using a new imaging technology called cryo-EM, the team was finally able to isolate and view the molecular structure of the channels Shyng had been studying for so long. It looked like a flower petal, or a bit like undersea coral. To Shyng, it was one of the most beautiful things she’d ever seen.

“It was definitely the most exciting moment of my scientific career,” she smiled.

For the first time ever, Shyng can see exactly where therapeutic drugs bind to the protein molecules that move potassium ions through these channels. That’s helping her design more targeted treatments for diseases like diabetes and epilepsy, with far fewer side effects.

Life beyond the lab

E.B. White once wrote, I arise in the morning torn between a desire to save the world and a desire to savor the world. This makes it hard to plan the day. Shyng says that’s a pretty apt way to describe her life, too. “I am inspired by science and passionate about my work, but I also think it’s very important to find balance. Otherwise you’ll burn out.”

Now that her kids are all grown and pursuing scientific careers of their own, Shyng spends her free time backpacking the local trails and cooking with her husband. (She says she’s particularly well known for her dumplings.)

With retirement in the not-so-distant future, she dreams of hiking the Pacific Crest Trail someday, and hopes to open a child care facility specifically for researchers.

“It’s so hard for young scientists who are struggling to care for their kids and build a career at the same,” she said. “I don’t think anyone should give up having a family just to pursue science.”

All that being said, Shyng said she’s not done trying to save the world just yet. “Once I find some new drugs that will fix these broken channels, then I’ll be happy,” she smiled. “Come back in five years and ask me how I’m doing.”

Learn more about the cryo-EM technology at OHSU

Meet a few of the other researchers at OHSU pioneering scientific advancements with cryo-EM