As the novel coronavirus spreads across the nation and around the world, it mutates. Understanding those different strains of the virus — and our immune response — is crucial. And knowing which strains respond to specific treatments is a vital part of managing the pandemic.

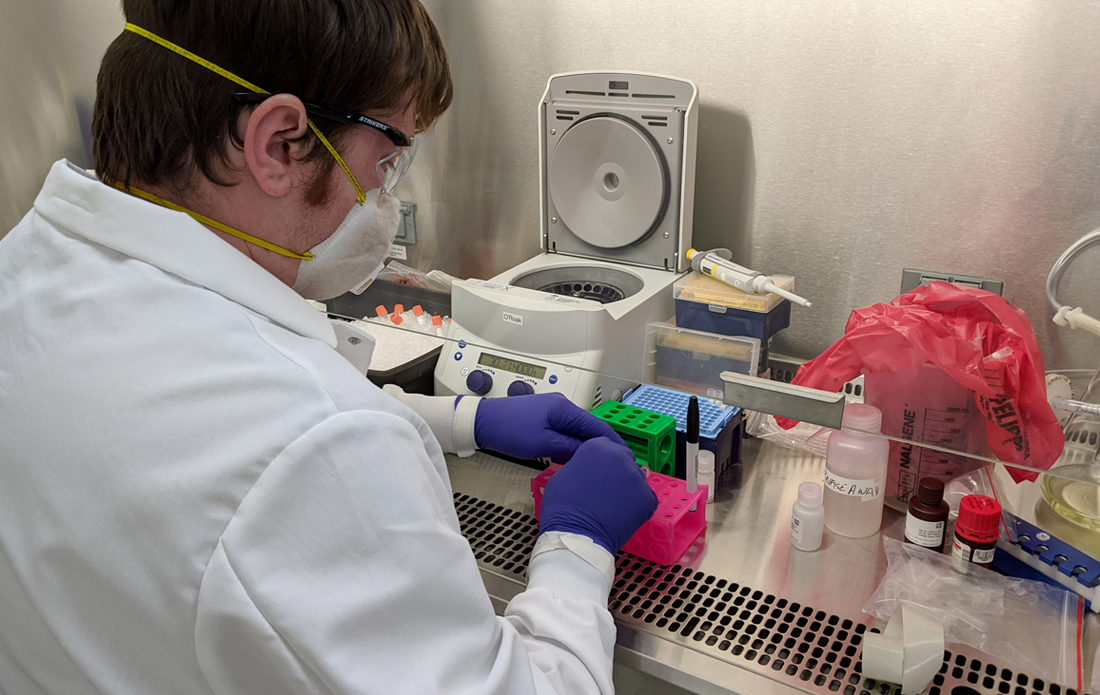

In mid-April, several OHSU researchers pivoted their labs to contribute to the global effort of tackling COVID-19. At the newly established Oregon SARS-CoV-2 Genome Sequencing Center, they began genome sequencing samples of the novel coronavirus from infected Oregonians across the state. And they made unexpected discoveries about how it made its way to Oregon.

The team is led jointly by: Brian O’Roak, PhD, associate professor of molecular and medical genetics, whose lab focuses on neurodevelopmental disorders; Andrew Adey, PhD, associate professor of molecular and medical genetics, whose lab applies single-cell technologies to study neurodevelopment and cancer biology; and Benjamin Bimber, PhD, research assistant professor, who studies the influence of genetics on infectious disease and the immune response.

We recently asked them about their work, how it can inform our evolving response to the pandemic and how they changed their labs to focus on this crucial research.

Dr. O’Roak, what is genome sequencing? Why is it important to understand the genome sequence of COVID-19?

Genome sequencing is a scientific method that allows us to see all parts of RNA from a viral sample and identify new mutations.

The instructions for making the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 are packed into about 30,000 bits or bases of RNA, which is the nucleic acid cousin of DNA. For some perspective, this is 0.001% the size of the human genome. Like all viruses, the genome of SARS-CoV-2 mutates, or changes, over time.

These new mutations are occurring about once every two weeks and can be used to build a family tree of genetically related virus samples. By linking with data from around the world, we can track how different viral families or transmission chains are spreading. We can also identify new mutations that might be important in terms of how the virus spreads or is responding to experimental treatments, which can be used to design new treatments or vaccines.

Your team continues to ramp up genome sequencing to learn more about the origins of COVID-19 in Oregon. What discovery has surprised you the most?

We were all really surprised how many different introductions of the SARS-CoV-2 virus there have been to Oregon at the start of the outbreak. Given our geographic closeness to the first U.S. case in Washington and discovery of community spread in the Seattle area in late February, we thought that most of the cases would be genetically linked to the Washington outbreak. However, we now know that SARS-CoV-2 was sneaking in to Oregon from all over the world and not just traveling down I-5.

Dr. O’Roak, your lab is focused on the genetic basis of neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism. How were you able to pivot your research to COVID-19 so quickly?

As a human geneticist, a lot of my work with neurodevelopmental disorders requires building relationships between the clinic and scientists from diverse backgrounds across OHSU and around the world. In our lab, we already had all of the equipment and lab ingredients needed on day one, but not the expert team we’d need or access to any COVID-19 positive samples. I think my prior experiences helped in building those key new relationships we needed to setup the Oregon SARS-CoV-2 Genome Sequencing Center.

Dr. Bimber, you’ve previously worked on the genetics of HIV. How has that helped the team understand COVID-19?

There are many technical similarities, which certainly helped our group quickly establish the assays and analysis pipelines. SARS-CoV-2 is very different from most viruses I study in that global sequence diversity is actually quite low.

It’s important to remember that SARS-CoV-2 was only introduced into the human population a few months ago, and has therefore had very little opportunity to evolve and diversify. It is my hope that we can apply lessons from other pathogens and use these changes to gain insight into the virus or the immune response against it. We are still in the very early days of this effort.

Dr. Adey, how has your lab adapted your genomic technology for COVID-19 work?

One of the driving forces in my lab is the ability to piece together different components of a variety of genomic techniques and adapt them to any new task or project. Previously, we used some of these methods to sequence poliovirus, another RNA virus. We were able to leverage that experience, the expertise of senior lab members Drs. Ruth and Brendan O’Connell, and our toolbox of genome sequencing methods to quickly pivot into SARS-CoV-2 genome sequencing. We are actively exploring alternative avenues to continue to improve our speed and efficiency to meet the needs of the time.

The MJ Murdock Charitable Trust has provided funding to support the group’s work in sequencing COVID-19 positive samples from across the state. And OHSU’s in-house COVID-19 testing lab was made possible by a gift from Nike leaders and Phil and Penny Knight.