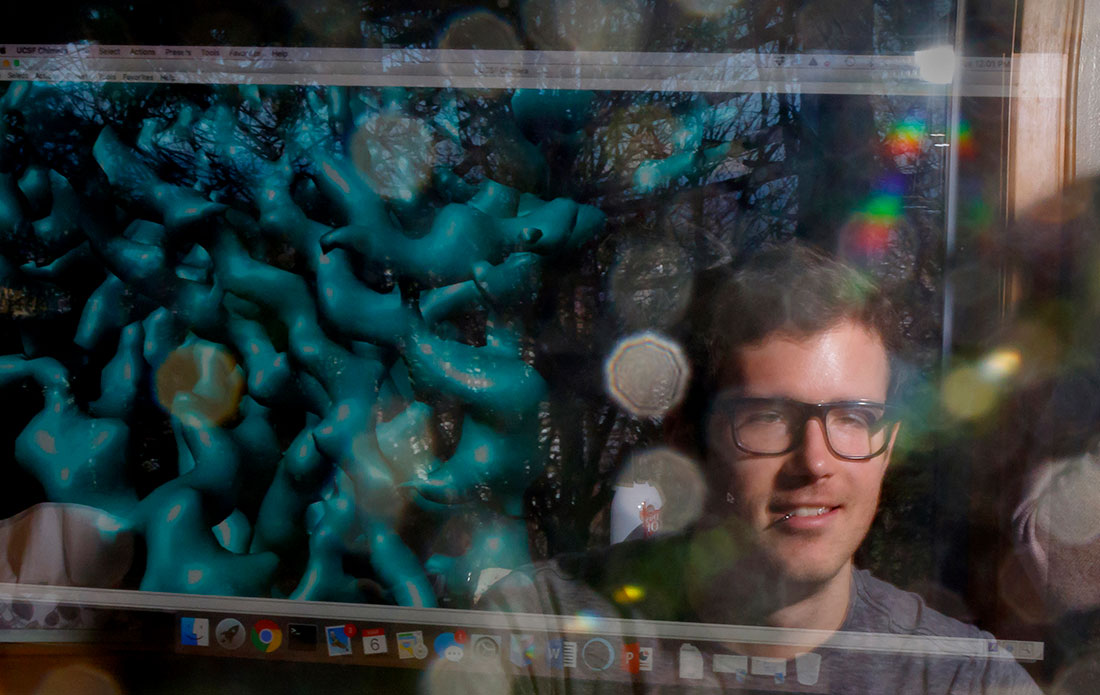

Imagine standing on the moon and looking through a telescope so powerful, you can see what someone on Earth is texting on their cell phone. That’s the type of analogy that can be made to describe cryo-EM, a new imaging technology being used at OHSU that allows researchers to zoom in on cells at nearly the atomic level.

Welcome to the next generation of imaging

Cryo-EM stands for cryogenic electron microscopy, and it’s changing the game for researchers across OHSU. Scientists can now examine the building blocks that make up our bodies with unprecedented clarity. The technology is so revolutionary that its creators were awarded the Nobel Prize in 2017.

In the past, scientists relied on an imaging technique called X-ray crystallography to view the structure of molecules. That came with some serious drawbacks, according to Peter BarrGillespie, PhD, chief research officer at OHSU.

“The problem with X-ray crystallography is that you need billions of molecules in your sample, and you also have to figure out how to organize them into crystals to get an image. That takes lots of playing around, and it can be hard to interpret the results,” he explained.

“It’s like blindfolding a mechanic and then asking him to work on your car. Cryo-EM allows you to see what’s happening — and when you see it, you can often figure out how to fix it.”

Eric Gouaux, PhD, Jennifer and Bernard Lacroute Term Chair in Neurosciences at OHSU’s Vollum Institute

With cryo-EM, all that’s required is a tiny sample that’s flash-frozen to protect it during observation. Because samples don’t need to be crystallized, they can be viewed “as is” in their native state. This allows scientists to see how proteins, nucleic acids and other biomolecules move and interact as they perform their functions. That could lead to groundbreaking treatments for diseases that are still poorly understood.

“It’s like blindfolding a mechanic and then asking him to work on your car. Cryo-EM allows you to see what’s happening — and when you see it, you can often figure out how to fix it,” said Eric Gouaux.

“In many cases, we don’t understand what’s going on with certain diseases because we can’t visualize it,” said Eric Gouaux, PhD, the Jennifer and Bernard Lacroute Term Chair in Neurosciences at OHSU’s Vollum Institute. “It’s like blindfolding a mechanic and then asking him to work on your car. Cryo-EM allows you to see what’s happening — and when you see it, you can often figure out how to fix it.”

Cryo-EM imaging has proven to be instrumental in Gouaux’s study of the nervous system. “It’s really changed the way that we understand how neurons communicate with each other and what happens when that process goes awry,” he explained.

Access for all

Gouaux is one of three principal investigators designated for the Pacific Northwest Center for Cryo-EM, which was established through a $42 million grant from the National Institutes of Health. It’s housed in a low-vibration microscopy suite in the Robertson Life Sciences Building and operated in partnership with the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

The Pacific Northwest Center for Cryo-EM is a major component of the OHSU-PNNL Precision Medicine Innovation Co-Laboratory. In 2018, OHSU and PNNL launched PMedIC, which provides experts at both institutions opportunities to collaborate on cutting-edge research. Partnerships such as this advance the practice of precision medicine and improve human health.

While the cryo-EM center is one of just three in the nation, OHSU is committed to providing access to as many scientists as possible.

“There’s a huge push to make this technology available to everyone,” said Gouaux. The process is remarkably simple: to access the microscopes, a scientist just needs to fill out a short application, which is reviewed by a panel of scientific peers. “If the request is reasonable, you’ll get time and training. In some ways, it’s almost easier than getting a driver’s license,” he smiled.

While getting approval is relatively easy, there are only so many cryo-EM microscopes to go around. (There are only 50 in the nation; five at OHSU.) They’re also wildly expensive to maintain.

“Purchasing the equipment is very costly. So is upkeep and staffing. The NIH is willing to devote some resources, but unfortunately they aren’t able to shoulder the entire burden,” explained Gouaux. “That’s why philanthropy is so important — we need donor support to keep the center operating at full capacity and capability.”

Gouaux added that it’s the generosity of donors that allows researchers to push the boundaries of what’s possible with cryo-EM.

“The projects that you might propose to do with this technology are really at the cutting edge,” he said. “Those kinds of projects don’t always receive government funding, because they’re viewed as too risky. However, breakthroughs often come from risk.”

Attracting the best and brightest

Besides all of the opportunities around research, the cryo-EM center offers another important benefit — it’s helping OHSU attract top-caliber scientists from all over the world.

“Having a national center for cryo-EM means that we are a nexus for investigators,” said BarrGillespie. “While any scientist with an approved project can use the center, having your lab at OHSU means that you’ll have easier access to the cryo-EM instruments and can collaborate with other users to take your research to the next level. Without a doubt, it’s a powerful recruiting tool.”