For the past 30 years, the OHSU Center for Ethics in Health Care has become a nationally recognized leader for end-of-life and compassionate care.

The heart of the center’s mission has remained constant: to change health care through compassion, integrity and innovation. Through the years, the center has created programs to teach and test students, aided OHSU faculty in mastering communication skills, conducted scholarly research and helped shape Oregon state policy.

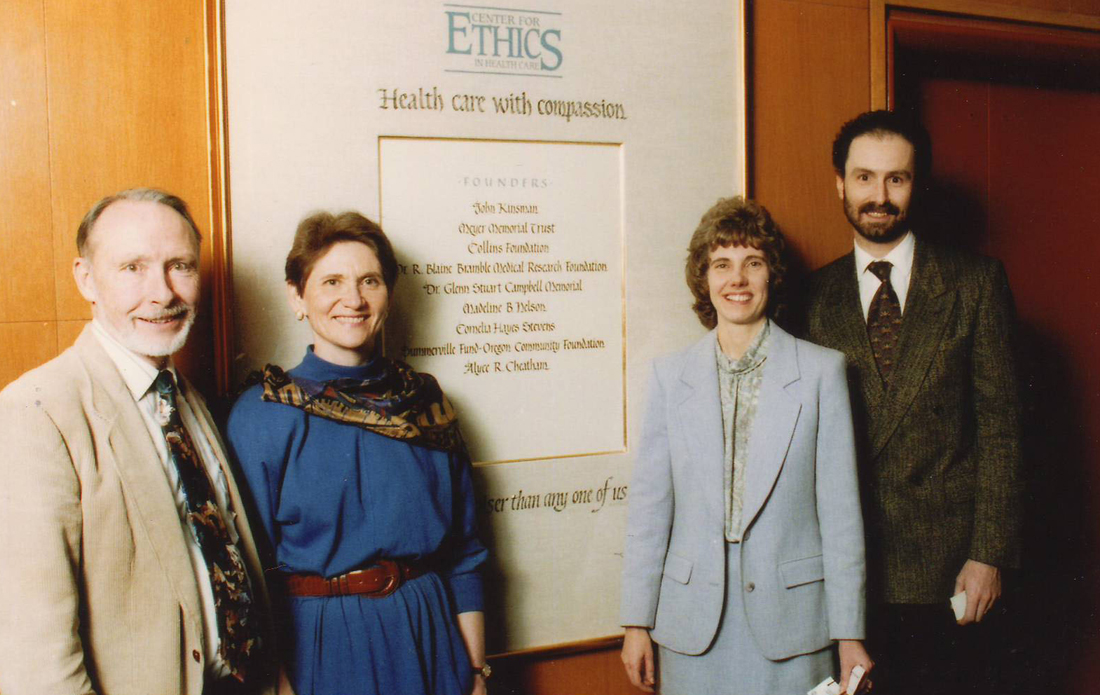

The OHSU Center for Ethics wouldn’t be where it is without Susan Tolle, MD, director of the Center for Ethics and the Cornelia Hayes Stevens Chair, who established the center with her colleagues in 1989. A recognized leader in her field, Tolle continues to play an active part in the evolution of medical ethics and has built the Center for Ethics into a flourishing resource at OHSU.

Susan Tolle, MD, is one of the leading voices for end-of-life and compassionate health care.

Transforming health care

In the early ’90s, many ill Oregonians often received unwanted medical treatment because they were too sick to vocalize their end-of-life wishes. Families would struggle with what to do: continue treatment or stop it.

The OHSU Center for Ethics quickly made this dilemma its flagship project in 1991 by creating the Oregon Portable Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment (POLST) program. This program gives patients control over their own end-of-life care if they later lose the ability to speak for themselves, often sparing families of making difficult medical decisions. The program is now used in every state in the nation and countries beyond, firmly establishing OHSU as a leader in improving end-of-life care.

After years of interviews with patients and families, Tolle started to notice trends with what can go wrong when delivering bad news — a physician may not make eye contact, they may stand in a doorway instead of sitting down with a patient, or they don’t pause to let information sink in.

“If you don’t deliver tough news well, the impacts can last forever,” Tolle said.

This led to the development of the compassionate communication program, which helps OHSU students master ethical and professional communication.

While many medical schools include communication training in their curriculum, OHSU was the first medical school in the country to develop ways of testing medical students’ communication skills as a requirement of graduation.

In addition to clinical skills, students must demonstrate how to deliver difficult news and communicate effectively and compassionately about emotional issues.

Students partake in a simulation in which they deliver a death notification to a professional actor who portrays a grief-stricken spouse. They’re recorded, then evaluated on how well they delivered the tough news.

“Communication becomes one of the most important tools to develop relationships between physicians and patients,” said Sophia Hayes, MD ’18, who took the test the first year of testing and passed. “The earlier you can learn these skills, the better you can assimilate them into the way you practice.”

“When doctors deliver bad news to their patients, every word carries meaning, and you need to choose your words very wisely.”

Susan Tolle, MD, director of the Center for Ethics

The center has continuously identified opportunities to ensure that health care is delivered in a way that honors and respects the needs of patients and families.

One of the most popular medical school courses the center has developed is Living with Life-Threatening Illness. Students are paired with a patient-teacher, a seriously ill person who helps students learn firsthand the difficulties of their journey. The class is intense and healing for the student and patient-teacher — each developing a meaningful relationship through the course of the semester.

That meaningful relationship includes Ron Naito, MD, who last year became a powerful patient-teacher after receiving an advanced pancreatic cancer diagnosis in a distressing way. He’s been an inspiring advocate for formal compassionate care education since.

With his diagnosis, Naito retired from his medical practice of almost 40 years. He’s dedicated his retirement to teaching compassionate skills to others, which includes building a program in serious illness education at the OHSU Center for Ethics.

“When doctors deliver bad news to their patients, every word carries meaning, and you need to choose your words very wisely,” Naito said. “All doctors can learn these skills, and the good news is that there are now excellent training programs available to support them.”

Leveling up

The OHSU Center for Ethics has thrived thanks to the philanthropy of many. More than 1,500 individual donors and foundations in the past 30 years have given generously in multiple ways. Ninety-five percent of the center’s funding comes from private philanthropy.

Two recent generous gifts have expanded the vision and accelerated the center’s work for the coming years.

Naito recently gave a $1 million gift to establish the Ronald W. Naito, MD Directorship in Serious Illness Education. The inaugural directorship is held by Katie Stowers, DO, a palliative medicine physician and assistant professor of medicine at OHSU, who teaches serious illness communication skills as well as advance POLST education.

“It has truly taken a village to build the center, and it is the power of a like-minded village that fuels our purpose and makes it possible for us to have the impact we’ve had in so many areas of health care.”

Susan Tolle, MD, director of the Center for Ethics

The Storms Family Foundation also donated a $1 million gift in support of the Program in Compassionate Communication Endowment Fund. This gift will help to expand the scope of the program to ensure more disciplines are receiving training in compassionate communication skills.

Multiple gifts have helped to fund numerous endowed positions. Much of the funding over the years has come from family members of terminally ill patients who had negative experiences with their loved ones’ end-of-life care and were inspired by the center’s work.

“It has truly taken a village to build the center, and it is the power of a like-minded village that fuels our purpose and makes it possible for us to have the impact we’ve had in so many areas of health care,” Tolle said. “Every gift is important, and we are beyond grateful for the dedication of our supporters over the years.”